Suffice to say that from an early age, perhaps thirteen, I was trained in the art of scepticism. This is a blatant fib. What I mean is that certain teachers, some of whom were considered subversive for their pains, introduced me to the art. The fact that they kept getting the sack did nothing to deter me. The authorities in my secondary school were so dodgy, I took the idea of scepticism and ran with it.

In some of the classes we had what they called ‘balloon debates.’ I was never sure about the balloon bit – my attention must have wandered momentarily when that was explained – but the principle of the thing was that you were selected to defend or attack a controversial view, such as the pros and cons of fox hunting. If that sounds hackneyed, it was a rural school; there were far worse subjects of controversy to be had. You then displayed your oratorical skills with equal pertinacity, whether you took the namby-pamby view that foxes ought to be treated in a humane fashion, or else you advocated that they be taken to a place of execution and ripped into as many pieces as a famished pack of beagles could contrive. With a skill like that, I might have gone on to become a lawyer or a politician.

Sadly, I lacked the gift for dispassionate eloquence. We can’t all be bastards. For one thing, it would obviate the concept of bastardy. The only bastards left would be actual bastards, like William the Bastard, though he complicated things by more than living up to his birth certificate.

After cultivating my scepticism in an environment (my school) that positively obliged any thinking person to doubt the legitimacy of anything, I arrived at a kind of climax in my thinking with the discovery of solipsism. I became convinced that I was the centre of the universe. Worse, that I was the only reality in the universe. I know, it sounds demented, but consider the rigours of my environment. Of course, it was not the most original conclusion for a sixteen-year-old to have reached, that my centre was nowhere and my circumference everywhere, but how many sixteen-year-olds really think it through the way I did? They mostly content themselves with being egocentric. Child’s play. Me, I thought, therefore I was. Besides, having the advantage over Descartes of possessing a youthful body pumped full of hormones, I also felt, therefore I was. In the end, as any life coach will tell you, it all comes down to self-belief.

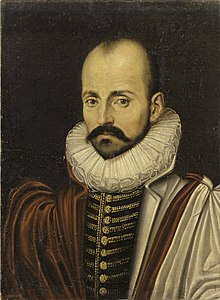

All this trawling of my past to say this: though I hadn’t heard of him back then, I was already primed to fall in love with Michel de Montaigne, and I don’t mean by mistaking him for a girl.

Anyone whose motto was ‘What do I know?’ would have fully equipped me to survive a Norfolk grammar school in the 1970s. What a pity he wasn’t there to hold my hand in the manner of Virgil guiding Dante through the inferno, I might actually have emerged half sane.

I think I first heard about Montaigne somewhat later, in relation to a translation of his essays by John Florio, a contemporary of Shakespeare. There is a strong possibility that the bard actually read the particular essay whose title I have stolen: a passage of The Tempest is lifted, virtually word for word, from Of Cannibals. I also wonder if Hamlet was one of Montaigne’s avid readers, given how closely the soliloquy resembles an essay. The very word ‘essay’ appears to have been Montaigne’s idea, derived from the French verb to try, and the soliloquys are clearly attempts to make sense of things, as well as being very inward. That inner musing, along with the open-mindedness that came from reading sceptics of the classical age, gives the essays their distinctive freshness. It’s the intellectual equivalent of that draught of beer after the trek across the desert in ‘Ice Cold in Alex’ (1958).

Yup, that is what you need after reading most philosophers. Try any of them if you don’t believe me. Try Heidegger, with the added bonus of being able to read his liberal apologists bending over backwards to excuse his politics. There is nothing pretentious or tendentious or obscurantist about Michel. He writes, somewhere, that you can put a man on the highest throne in the world, he still has to sit on his arse. With attitudes like that, it’s obvious what a dim view Heidegger would have taken of him.

It helps that Montaigne was not an academic. He had far too strange an upbringing (having to speak Latin with his own parents, par exemple) to wish that on himself. But he was studious, as well as unafraid of his own company. The tower where he worked still survives. Overhead, on the ceiling of his study, tags and mottos were painted along the beams. According to the Wikipedia entry on his room the walls were once decorated with paintings of mythical scenes, like Venus with Adonis, Venus discovered by Vulcan having it away with Mars, Venus in the Judgement of Paris, Venus… You get the picture. I can almost hear the estate agent: “Here we have the study. Of course, nowadays a more neutral look is in favour.” The Wikipedia entry rather coyly attempts to explain this wall-to-wall sauciness:

‘One of the central themes of the paintings gathered in the space seems to have been nudity, a question metaphorically at the heart of the writing project of the Essays’

Yeah right. I don’t know, was the man made of flesh and blood? Because if you surrounded me with this kind of thing, it would definitely not be calculated to keep my mind on my homework. I suppose it accounts for his lack of apparent prudishness when it came to the nakedness of the Brazilian natives. For all I know, he sat at his desk in his birthday suit. Somehow, despite these adverse conditions, Montaigne managed to keep his mind on his work, thus demonstrating that not all Renaissance types were as bad as Raphael.

In fact, so fond was the Frenchman of his solitary studies that he retired from the world in his late thirties to pursue knowledge. Unlike a similarly sequestered genius of our age, he did not emerge to wreak havoc in the civil service. He did his public duty when called upon, and otherwise he enjoyed his own company. Despite being a devout Catholic, he would skip mass when he was busy, though he made sure he was able to hear it through ‘conduits’ connecting his study to a nearby chapel.

At least, this is what I’ve been able to glean from my own extensive and largely solitary reading, hidden from the world and living on a diet of ready-made M&S chicken curries. This modest lifestyle makes Montaigne look like Boy George on a Friday night. But conduits? Maybe. In all candour, what do I know?

On a visit to Rome in later years, this (fairly) good Catholic would present his collected essays to Sisto Fabri, who served as Master of the Sacred Palace under Pope Gregory XIII. Montaigne asked to be forgiven for referring to the pagan notion of Fortuna quite so much. Oh, and for being far too soft on Julian the Apostate. Now Fabri was acquainted with Giordano Bruno, a man who would not have known he was awake unless he’d referred to Fortuna and been soft on Julian the Apostate several times before breakfast. Perhaps mildly disappointed, Fabri sent the essayist away with the instruction to follow his own conscience.

This was not particularly helpful advice and certainly didn’t justify the long journey to Rome. Montaigne had a natural inclination to follow his own conscience. It was this same inclination that had led him to write the book in the first place. Still, he could console himself that he hadn’t been excommunicated for heresy. In those days, you wouldn’t want to upset the Master of the Sacred Palace.

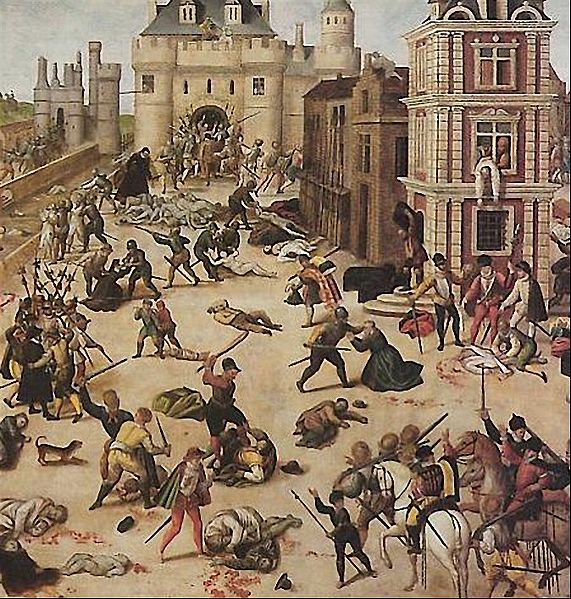

I say ‘in those days’ because these were turbulent times by any standards. For most of the essayist’s adult life, the country was caught up in what came to be known as the religious wars. The seventh of these was raging at the time of his book’s publication. Three million people are believed to have perished, through violence, famine, or disease in the struggle between Catholics and the Huguenots (who were Calvinists), and atrocities were committed by both sides. However, just eight years before the essays became available, the St Bartholomew’s Massacre had shaken Paris and other French cities. For three days, anarchy reigned in the capital as Protestants were rounded up and butchered – men, women and children – and their bodies dumped in the Seine. Christopher Marlowe found the events so shocking he wrote a play. Even Ivan the Terrible deplored the violence. Philip II of Spain, on the other hand, ‘laughed, for almost the only time on record.’

One can easily imagine Montaigne’s reaction. He was as humane temperamentally as he was humanist intellectually. Equally respected by the heads of the warring factions, King Henry III (Catholic) and Henry of Navarre (Protestant), he was unimpressed by the ‘passionate intensity’ around him, but the retiring philosopher was in a potentially compromising position. With Jewish grandparents on both sides and a mother who had converted to the Protestant cause, a desire for compromise must have come naturally to him, but there was more to this than a healthy instinct for self-preservation. In the essay Of Cannibals, he notes how ‘everyone gives the title of barbarism to everything that is not in use in his own country.’ Whenever he makes explicit comparisons between the so-called ‘savages’ and the violence of his ‘civilised’ countrymen, the latter appear more barbaric:

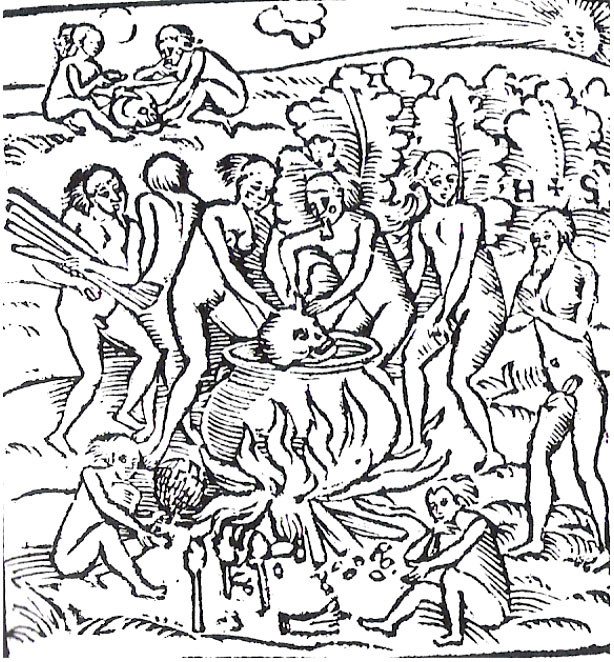

‘I conceive there is more barbarity in eating a man alive, than when he is dead; in tearing a body limb from limb in racks and torments, that is yet in perfect sense; in roasting it by degrees; in causing it to be bitten and worried by dogs and swine (as we have not only read, but lately seen, not amongst inveterate and mortal enemies, but among neighbours and fellow citizens, and, which is worse, under colour of piety and religion), than to roast and eat him after he is dead.’

He takes eating in a wider sense here, as a form of killing by increments. In a further aspersion on his own times, he wishes that the ‘savages’ in the New World had been discovered long ago, when people like Lycurgus and Plato were still around, since the happy simplicity of their lives far exceeded the Golden Age of the ancient poets and the best attempts of philosophers to imagine a perfect society. The implication is that no one now living in Europe could have the intellect, or perhaps the decency, to see this perfection for what it is, let alone emulate it, so far had civilisation degenerated.

Of Cannibals is not a neutral ethnographic essay. It is a bitter satire on Montaigne’s supposedly Christian contemporaries who, despite a professed love of God, are nonetheless ready to treat each other so cruelly. In a sign of the divisions that prevailed, the Frenchmen who wrote about the tribes they had encountered on the shores of Brazil came from opposite sides of France’s religious war. André Thevet, whose book ‘The New Found World’ came out in 1572, was a Franciscan priest. Jean de Léry, who published his ‘History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil’ in 1578, was a Protestant Huguenot. The religious conflict had followed Léry across the Atlantic, forcing him to take refuge with the Tupinambá and thus perfectly illustrating Montaigne’s point about the relative barbarism of Europeans. Thevet may have been the first European to describe the peanut, but he also had personal experience of the Tupinambá tribe and spoke of the way they treated their captives before tucking into them:

‘On the final day before his or her execution, the prisoner is chained to a bed and is the subject of a ceremony in which community members gather and sing of their death. Finally, the condemned man or woman is brought to a public place, tied up, hacked to pieces, and consumed by the local populace.’

The same thing happens to any children these prisoners had sired in the meantime. Montaigne mentions the prisoner being despatched with swords, but, apparently, he preferred to pass over the issue of his offspring. Insufficiently Arcadian, perhaps, or else he was just more sceptical than his fellow Catholic.

In the midst of a vicious civil war, it is hardly surprising that the attitude of the natives to violence of this sort fascinates Montaigne. He clearly admires their valour. They are fearless in battle:

‘The obstinacy of their battles is wonderful, and they never end without great effusion of blood: for as to running away, they know not what it is. Every one for a trophy brings home the head of an enemy he has killed, which he fixes over the door of his house.’

If they are captured, however, it is entirely beneath them to entreat or beg for forgiveness. They would far rather be killed and eaten than show any cowardice in the face of death. This valour of the Tupinambá relates, crucially, to their motives for making war:

‘If their neighbours pass over the mountains to assault them, and obtain a victory, all the victors gain by it is glory only, and the advantage of having proved themselves the better in valour and virtue: for they never meddle with the goods of the conquered, but presently return into their own country, where they have no want of anything necessary, nor of this greatest of all goods, to know happily how to enjoy their condition and to be content.’

The essay is very insistent on this, as if its writer knows the reader will scarcely be able to get their head around the idea:

‘Their disputes are not for the conquest of new lands, for these they already possess are so fruitful by nature, as to supply them without labour or concern, with all things necessary, in such abundance that they have no need to enlarge their borders. And they are, moreover, so happy in this, that they only covet so much as their natural necessities require.’

This lack of any concept of gaining territory or booty by war, owing to the complete sufficiency of their existing resources, means there is a moral purity to their aggression. It is based entirely on a desire for glory. In keeping with the polemical thrust of his essay, Montaigne insists on such ideal qualities. They do a lot of dancing and singing, and not a great deal of labour. They are artless because they have no need of ingenuity. This is crucial to the argument, as Montaigne sees little value in European expertise:

‘Our utmost endeavours cannot arrive at so much as to imitate the nest of the least of birds, its contexture, beauty, and convenience: not so much as the web of a poor spider.’

His disdain for art is founded on a satirical contrast with ‘mother nature,’ and this leads to an upturning of the usual dichotomies, so that

‘…they are savages at the same rate that we say fruits are wild, which nature produces of herself… whereas, in truth, we ought rather to call those wild whose natures we have changed by our artifice and diverted from the common order.’

Thus, according to this reasoning, cultivation has created aberrant phenomena, and a countryside that has little of nature left in it. Human intervention has upset the order of nature. This is a radical rejection of civilisation in all its smugness. And then we get this – the passage that may well have caught Shakespeare’s eye and which still has the power to arrest us now. He is describing the life of the Tupinambá in negative terms here, according to what they do not have:

‘there is no manner of traffic, no knowledge of letters, no science of numbers, no name of magistrate or political superiority; no use of service, riches or poverty, no contracts, no successions, no dividends, no properties, no employments, but those of leisure, no respect of kindred, but common, no clothing, no agriculture, no metal, no use of corn or wine; the very words that signify lying, treachery, dissimulation, avarice, envy, detraction, pardon, never heard of’

This idealism is not only familiar from The Tempest. It smacks of a long tradition. Voltaire’s utopia will also be set in the Americas, as will Samuel Johnson’s, but the one utopian writer who might be said to have beaten everybody to it was Thomas More. In his book, which gave us the very word ‘utopia’, people live the simple life and gold is employed to fetter criminals, or even to make chamber pots, thus instilling a proper contempt for the material. In Candide, the citizens of El Dorado use precious jewels to pave their streets. The purpose of the ideal of a society in harmony with nature was to counter the moral decline of a civilisation where amassing great wealth had become the sole motivation. Even as the Europeans were pillaging the newly-discovered continents, their moralists were questioning the fundamentals of colonialism.

But to this day, the descendants of those first European visitors have not had their fill of gold. Tens of thousands of ‘garimpeiros’ (artisanal gold miners) are threatening the lands of the Yanomani tribe whose territory straddles the borders of Brazil and Venezuela. Gold mining is a filthy and destructive business. Clearings are cut into forests, mining ponds are carved into the earth, and the mercury used in extraction is dumped in rivers, poisoning fish stocks and water supplies. Almost all this mining is illegal, but Bolsonaro, the new Brazilian president, has expressed far more support for this group than previous state leaders. It is to some extent a personal issue – Bolsonaro’s father was a part-time gold miner, and the president has said he himself panned for gold while serving in the army.

“Bolsonaro is a garimpeiro,” says Davi Kopenawa, shaman and leader of the Yanomami tribe. “It explains the way he thinks, always trying to explore more land. He has a sickness in his head. He doesn’t think about others, or about the future.”

Kopenawa is arguably the most prominent voice of the more than three hundred different indigenous groups in Brazil. He has been to the West and seen for himself some of what Montaigne was describing, hundreds of years before. Here, for instance, is the shaman’s verdict on New York:

‘Multitudes of people move very fast […] They look at the ground all the time and never see the sky. Yet while the houses in the centre of the city are tall and beautiful, those on its edges are in ruins. The people there have no food and their clothes are dirty and torn. They looked at me with sad eyes. These white men are greedy and do not take care of those among them who have nothing. How can they think they are so smart? They do not want to know anything about these needy people. They reject them, and let them suffer alone. They are happy to keep their distance and call them “the poor”.’

It is almost as hard to imagine Montaigne in modern New York. He would have had no difficulty empathising with the sentiments of a visiting forest-dweller. Apparently, there still lingers – in some remote places, peopled with ignorant idealists! – the assumption that property should be held in common. The French sceptic was one of the first, and one of the very few, people in the West who could hear the voice of a happier past, before his species was split in half and estranged from its fellow humans, not just over religious differences, but existentially, as if occupying two different planets:

‘…they have a way of speaking in their language to call men the half of one another [and they] observed that there were amongst us men full and crammed with all manner of commodities, whilst, in the meantime, their halves were begging at their doors, lean and half-starved with hunger and poverty; and they thought it strange that these necessitous halves were able to suffer so great an inequality and injustice, and that they did not take the others by the throats, or set fire to their houses.’

There, in one long-dead cannibal’s words, is the rationale behind gated accommodation.