In the last two months, widespread protests over a controversial new citizenship law in India have raised the prospect of a constitutional crisis. Those protesting the law—which for the first time determines Indian citizenship on the basis of religion—see it as emblematic of growing authoritarianism and Hindu majoritarianism. They claim that Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist government threatens the founding secular vision of India by bullying and marginalizing minority Muslims. At demonstrations, they brandish copies of the constitution.

India’s constitution, which turned 70 years old in January, promised that the state would treat all Indians as individuals with inalienable rights, not group them into communal categories. Though religious identity has played an important role in Indian politics since independence, the constitution’s universal guarantees have protected minority groups. This past week, the trustees of a Sufi shrine in Mumbai commemorated the 607th anniversary of the death of their revered saint by unveiling a plaque engraved with the preamble of the constitution.

It remains to be seen if the growing civil unrest can be channeled into a viable political challenge to the government, but the dispute has opened up a larger conversation about the origins and character of Indian democracy. The constitution that the protesters seek to defend grants universal suffrage to a people that had, for centuries, been seen as too poor, diverse, and fractious for self-rule. Its current travails are a reminder of the unique—and precarious—foundations on which Indian democracy rests.

India is, as the political theorist John Dunn recently put it, “the most surprising democracy there has ever been.” The country has achieved self-government in the face of daunting poverty, sustained relative peace amid diversity, and managed the persistence of regular elections despite abuses of power. But the conditions of its birth make Indian democracy unlikely and unprecedented. The struggles and movements that brought democracy to India in the twentieth century weren’t echoes of the great revolutions of late-eighteenth-century Europe, as many scholars have assumed. Instead, the writing of India’s constitution represented a singular event, a moment when democracy had to create the conditions for its own existence.

NEW TRADITIONS

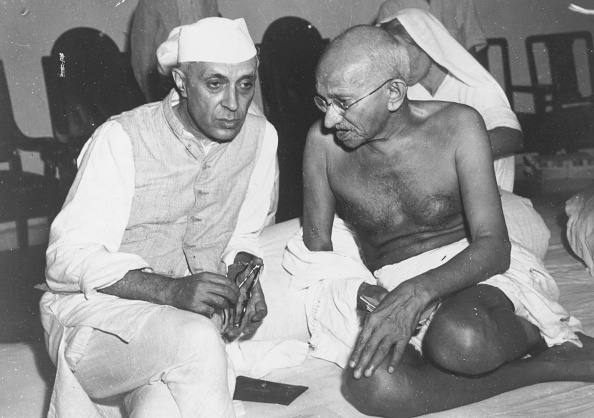

Few Westerners around the time of India’s independence in 1947 thought democracy was advisable or even possible for the country. “The general tradition in Asia,” British Prime Minister Clement Attlee wrote to his Indian counterpart, Jawaharlal Nehru, in 1949, “is in favor of monarchy.” Attlee’s sweeping generalization of Asian political culture was not an offhand note of condescension. The belief that democracy was suited only to certain parts of the world—the countries of the advanced and “civilized” West—endured from the nineteenth century well into the twentieth century and even, in some quarters, into this one. Many Europeans shared Attlee’s concern in one form or another. When the University of Cambridge scholar and lawyer Ivor Jennings traveled across South Asia after India and Pakistan won independence, he advised the makers of the new nations to limit the electoral franchise in the interest of maintaining political stability; instead of opening the vote to all, Jennings recommended a “narrow franchise, indirect elections, [and] tribal representation.”

In the eyes of Jennings and others, the inhabitants of India were not like the citizens of Western nation-states where democracy flourished. India was a poor and illiterate nation, torn apart by caste and religion and encumbered by centuries of custom and tradition. In western European countries, democratic institutions and practices had evolved gradually over centuries as wealth and income rose, and the franchise was slowly extended to all. But in the postcolonial world, already deemed inhospitable to liberal self-government, independence and democracy arrived at once.

Nehru, India’s first prime minister and one of its founders, called the question of democracy’s suitability to the country “the Indian problem”—and his answer met colonial assumptions head-on. In Nehru’s view, the British had put the cart before the horse. Democratic citizens weren’t needed to produce democratic politics. Instead, democratic politics could produce democratic citizens. Nehru believed that installing the right political structures would give rise to the practices of self-rule that sustain a democratic system. This rejection of the imperial vision of governance in India affirmed that one’s world could be made and remade through politics.

Nehru and other framers of India’s constitution took up the difficult task of creating a process through which Indians would become democratic constituents. Their vision had several defining features. The first was an explanation of the rules that could make collective political life possible. In a land with little shared understanding of democracy, Indians needed to learn a new language. A constitutional text could provide common meaning—laying out the definition of rights, for example, or setting the responsibilities of the state, it instructed the grammar of self-governance. The founding document, the world’s longest constitution with nearly 400 provisions, also cataloged the norms underlying democracy. Many scholars at the time noticed the constitution’s remarkable length and felt that it represented something different. The German theorist Carl Schmitt, for instance, noted that the text was a far cry from “the type of constitution on whose foundation past European constitutional law and . . . the separation of powers were formed.” In the West, constitutions assumed the presence of ingrained norms and laid out a map for navigating them. In India, by contrast, the constitution had to create those norms from scratch. India’s constitution couldn’t simply be a rulebook—it also had to be a textbook.

In addition to laying out the rules, India’s constitution enshrined the centrality of the state. For B. R. Ambedkar, a central figure in the drafting process, India’s villages had led to “the ruination of India.” They were “a sink of localism, a den of ignorance, narrow-mindedness, and communalism.” Only a strong, centralized state could counter the negative effects of Indian social traditions and place all Indians in a new, equal relationship with one authority. Both Nehru and Ambedkar agreed that Indian society lacked the civic spirit that enabled democratic government elsewhere. Where they differed from British imperialists was in believing that this democratic deficit was only contingent; a new politics could usher in a new kind of people.

MAKING THE CITIZEN

The final, crucial element of the constitutional architecture was its concept of the citizen. In the years leading up to the partition of British India and the end of colonial rule in 1947, several competing proposals emerged for how to imagine citizenship. Few centered on the individual. Both Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the eventual founder of Pakistan, and Hindu nationalists sought to mediate citizenship through membership in religious groups. Their emphasis on communal attachment was inherited, in large part, from a century of British colonial politics that imagined India as an amalgam of groups with permanent identities rather than a land peopled by individuals with agency. For decades leading up to partition, colonial authorities had experimented with a variety of constitutional schemes that assumed religious identity was the primary category of political belonging. From the Morley-Minto Reforms of 1909 until the end of colonial rule in 1947, the British treated Hindus and Muslims differently, through arrangements ranging from separate electorates to reserved quotas to the principle of “weightage” (in which minority groups would receive representation in excess of their population). By contrast, Nehru and other secular nationalists minimized the importance of religious identity, arguing that economic concerns were the real drivers of social conflict.

Partition changed everything. The cleaving of British India into a Muslim Pakistan and a secular India not only forced the largest migration in human history (with around 15 million people displaced and over one million killed) but also drove home the failure of political arrangements centered around group identity. The division of territory had, after all, occurred after decades of trying to manage different communities through a variety of colonial administrative and legal frameworks. For India’s founders, the colonial model of representation had made certain religious differences politically salient—it had demonstrated how an emphasis on communal representation could create its own grisly reality.

Having witnessed the catastrophe of identity-based politics, the makers of India’s constitution sought a model of representation centered on the individual that could both ensure freedom and build a sustainable democratic political environment. Retaining group-based modes of citizenship, they believed, would condemn Indians to medieval forms of association and bondage. The constitution thus rejected the colonial model of citizenship, emphasizing the importance of the individual vote. It did away with separate electorates, weighted representation, and reserved quotas on the basis of religion. In doing so, it promised to allow Indians to exercise agency and perform deliberation. It would make them modern in the sense that they could construct their political reality through free and conscious decisions. By subjecting Indians to a new world of rules, by locating them under a single authority, and by placing them in a framework where they encountered one another as individuals, the constitution would convert Indians from subjects into citizens.

For much of the past seven decades, Indian constitutionalism has succeeded. Barring a few exceptions—most famously, the 18-month period between 1975 and 1977 known as “the Emergency,” when Prime Minister Indira Gandhi curbed civil liberties—India’s political elite and its people have remained committed to the principles of the constitutional text. The most revealing feature of India’s success has been the fact that few social conflicts in this country of over one billion people have assumed an extraconstitutional form—through armed insurgency, for example. By and large, every major political conflict in modern India has taken on a constitutional character, waged within the bounds of the system erected by the constitution’s framers.

Whether this will remain true in the future is an open question. However influential, the constitution has not convinced all Indians; Hindu nationalists still aspire for a model of citizenship and belonging defined by religious identity. The erosion of democratic and constitutional norms under Modi’s government—from the curbing of freedoms in Kashmir to the growing silence of the nation’s Supreme Court, which has refused to hear even habeas corpus petitions, to the ongoing dispute over the citizenship law—may well result in fewer and fewer adherents to the constitutional project.

THE PROMISE OF POLITICS

As India’s democratic order faces numerous pressures, its founding moment is a reminder of what politics can achieve. In India today, there are real fears over changes to the country’s secular character, the collapse of public institutions, the elimination of checks and balances, and the emergence of unbound state authority. Nationwide protests since December suggest that the country is reckoning with challenges to its ideals of self-rule. This process will require recovering the sense of political possibility that India’s founders envisioned. Mohandas Gandhi, Nehru, and Ambedkar shared a belief that Indians could make and remake their world—and the world that they wanted to create was one where individuals would be treated as free and equal. For them, it was important to guard against not only authoritarianism but also cynicism.

The promise that modern India can be constructed and reconstructed is at once gratifying and terrifying. It led some such as Nehru—who cemented Indian democracy during its delicate early years—to believe that self-government needed careful and constant tending, that it could go just as it had come. The making of the Indian republic was driven by an understanding that, for better or worse, one’s ideological vision can give rise to its own reality. Today’s protesters—the thousands who have assembled in streets and parks across India—understand that. They recognize the radicalism and substantive vision of India’s founders. For those demonstrating against the government, the constitution is a reminder both of the meaning of equality and freedom and of the possibility and dangers of political change. India was fashioned 70 years ago in a moment of startling originality, but it can be remade in ways that depart perilously from the original vision of its founders.

This article was originally published on ForeignAffairs.com.