‘Boris Johnson and Jeremy Corbyn have at least one thing in common – a lot of people think each is unfit to be prime minister and many of those believing this belong to their own tribe’ (my italics, 10 November 2019)

So it seems appropriate that the National Gallery is staging a Gauguin exhibition, and that Channel Four has been treating us to a simple tale of everyday British folk whose house is replicated in the middle of the Namibian desert and they are woken up (to the dismay of the male of the group) by a cock crowing and a view of mud huts as far as the eye can see. The controversy over Gauguin is so well-rehearsed that the National Gallery took it as read – just a routine case of the exploitative colonialist hiding in plain sight – but if you wanted real, live controversy, of a kind that doesn’t just set the social media abuzz with inanities, but which receives a full-throated chorus of harrumphing from every liberal-minded columnist who gets wind of it, you would undoubtedly choose The British Tribe Next Door. What were they thinking? Or smoking, as the Independent put it. The programme was so utterly, predictably bad, it caused outrage even before it came on. Sometimes, with a fast-moving media churn like we have today, the only guarantee of getting heard is to speak up before a thing’s actually happened. Ideally, opinion writers are already outraged by the next scandal; the present one’s old news. Thus, Afua Hirsch condemned the programme, sight unseen, as a hopelessly misbegotten exercise in reverse anthropology, hence the use of the phrase ‘British tribe’. She felt compelled to pitch her own version instead:

‘I have an idea for a British TV series. It involves finding an African society with a history of regarding Europeans as a profoundly inferior race… Then find a small-town family, from County Durham, say, to perform stereotypically “English” culture to entertain them… but make sure the African characters are equipped with various gadgets and a familiar value system. We’ll follow their love lives, clothing preferences and personality quirks in minute detail’ (Guardian, 28 August 2019).

The aim of all this would be the avoidance of what Hirsch calls the ‘tits and spears’ account of African life. You don’t visit a semi-nomadic tribe in Namibia if you have issues with bare breasts and spear carrying; you head for the chic boutiques of Senegal where the kids all have smart phones. The worry is that, just possibly, you’ll find an unhealthy vogue for skin bleaching. At least the spear carriers have a proper disdain for modern life.

But, according to Gaby Hinsliff (also in the Guardian), that’s the nub of the problem. The programme – which she actually watched, through her fingers one imagines – peddles ‘the spectacularly dated myth that all Africans live in mud huts and wear tribal dress’. We see the tribe’s poverty and simplicity through a romantic lens. It’s all of a piece with idealising the poor, or the asceticism of monks (I’ll come to that in a second) or the old cliché of the noble savage, Henry Thoreau and (cue cringes) The Good Life.

Others were less forgiving. The Independent called it anachronistic and condemned its ‘implicit’ racism. There’s only one thing worse than the implicit kind. The New Statesman, meanwhile, railed against ‘possibly the most offensive reality TV programme to have been aired this side of the Millennium.’ Whoa, steady on. We are talking about a genre most liberals consider an abomination, and this is worse than any of that? I predict it will be very goggled at indeed, in that case – we could be looking at the idea that dragged the under-forties back to the boring old goggle box, heralding the end of smart phones as we know them.

It’s for words like ‘implicit’ that I read the opinion writers so avidly. That and the interior monologue of the liberal voice of the nation that starts by discussing a tribe in distant Namibia and ends by referring to an ancient sit-com that involved middle class people abandoning the rat race to rear goats in their back garden. There really are people who live in mud huts. There are plenty of others that don’t. Personally, having seen them for myself, I have never quite got over the desire to move to one of these huts at some point, when the life in England finally becomes unbearable. I could use a little of the Himba attitude to life as well. They seem humorous, in a candid sort of way and, as I always hoped, very vain about their lifestyle and appearance. The women try unsuccessfully to induct La Moffatt into their aesthetic, which involves a lot of ochre, no bras, a leather skirt that wouldn’t be out of place on the Kings Road in the late Sixties, but she is too shy.

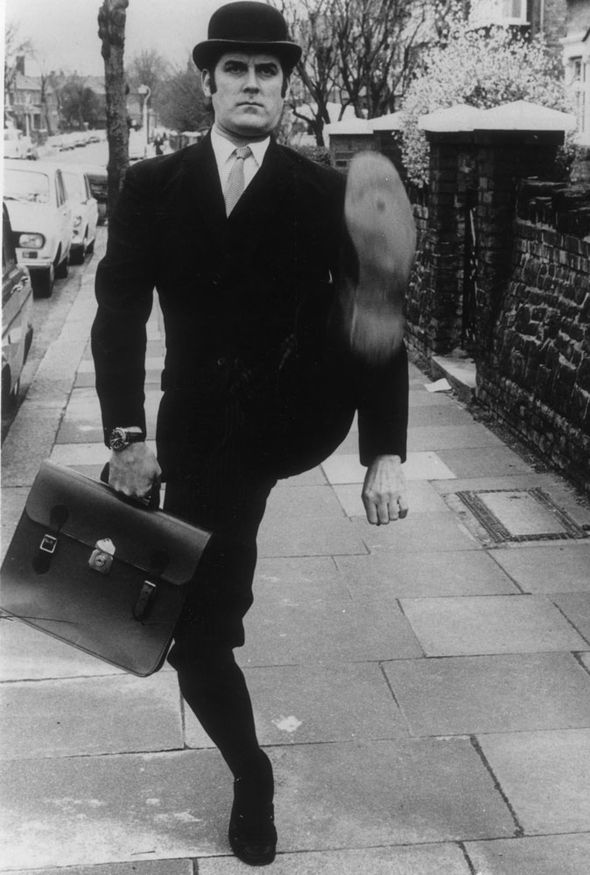

Meanwhile, their menfolk are candidly alarmed when the male of the British family is given some cows to look after and promptly loses them. There are interesting revelations about polygamy, numerous lovers on the side, a conviction that England is a place of eternal winter. I don’t see what’s so racist, even implicitly, about a British family getting to know some people with a different skin colour who live entirely different lives. Everyone gets on famously once the cows are recovered and the Englishman successfully identifies the ones he mislaid. I mean, yeah, it was a damned silly idea to build a replica of a British house in the desert. But we can be a silly bunch in more harmful ways than that. We’re Love Island, after all. We’re the ones who, having become an entire continent’s favourite destination, suddenly preferred to be its pet hate. We’re punks. We’re drama queens. Like that curmudgeonly defector, John Cleese, we used to walk silly walks, now we talk silly talks.

And who could say we haven’t got a lot sillier lately? Any Himba woman would find the joke rapidly wearing thin if she had to spend a month in Durham, even if they gave her a replica mud hut made out of plywood for her stay. ‘There must be something in the water,’ she’d sigh. ‘God knows, I’ve seen plenty of that element in recent weeks. They say that, even by local standards, there’s been a very great deal of rain. Mind you, I reckon I could get used to it with time, but this slow drip, drip of liquid from the heavens is accompanied by the even slower, infinitely more annoying drip of their politics. They’re all so grumpy the whole time. They’re divided into more tribes than you can shake a spear at. I thought the British people were supposed to be tolerant and friendly, but they scarcely even emerge from their little hovels. They live like troglodytes in their caves where the only sound is of stalagmites growing, very slowly, in the dark. It really is the land of eternal winter. I can’t wait to get back to the desert and having to fetch filthy water from a hole in the ground, ready to jump out if a snake appears. I’ve had enough reverse anthropology to last me a lifetime.’

The Himba woman would be right, of course. The most commonly heard phrase these days is a month’s rainfall in one day, as if the climate itself wanted to get things over with and move on to the next scandal. The effect has been like Chinese water torture for an entire nation, estranging us from what few wits we ever had, and all compounded by a certain catastrophic meteorological event called Brexit. Sometimes it seems this was the real purpose of the referendum: to replace every other topic of conversation. People have even given up speaking about the weather. Speaking about the ‘climate’ doesn’t count, and besides, unless they are gluing themselves to some means of public transportation or other, they tend not to express an opinion on the climate, as it’s become hopelessly political. In fact, they hardly dare speak of anything, for fear of getting someone’s back up.

I remember reading once that Trappist monks, the ones who observe a strict vow of silence, do say the words “Soon, brother, soon!” when they meet. This condensed utterance can be interpreted thus: “Soon, brother, this seemingly interminable labour of existence will be at an end and we can shuffle off into eternity, a blessed release that cannot come too soon, if you ask me, because in all honesty, I’ve had just about enough of… etc.”

This would then be followed by a long list of complaints – about the food, the company, the cold nights, the dog Latin, the lack of basic creature comforts, the thankless grind and the whole concept of serving as a lightning rod for the sins of the laity. It would be exactly like the first interview that Harpo Marx gave after long years of pretending to be a mute and communicating with toots on a horn. The hapless interviewer couldn’t shut him up. Equally, it really isn’t any surprise that the Trappists are so laconic (see my note on this word at the end of the article) – it’s a choice between that or a potentially endless stream of verbiage. The motto over the doors of their monasteries should be ‘Don’t get me started!’

This is the predicament we Britons are in: like Brexit monks, we are dying to blurt out our complaints, but we have divided into two tribes whose complaints are diametrically opposed. The remain voters want to complain that the leave voters got us into this appalling mess, while the leave voters want to accuse the remain voters of being obstructive and lingering out the agony. Whatever way you look at this, it doesn’t offer promising material for the country’s customary pastime of cheerfully directionless conversation.

And yet, when people do actually speak, which is an increasingly rare occurrence, they cannot resist talking about Brexit. It’s the return of the repressed, an act of defiance against the Brexit superego. Like children in bunk beds with strict orders to stay quiet after the lights go out, they cannot resist chattering, only being adults, they do so in a circumspect way. To avoid raising any hackles, they grumble that Brexit hasn’t been settled yet, without revealing how they would like it to be settled.

British politeness. Permit me to digress briefly on that thorny topic. You see, the concept of two tribes in Britain is not as novel as it seems. The country regularly splits in two at the slightest provocation, bifurcating over almost every subject that comes up. Correction: every subject. There is a Tory position and a Labour position on everything, from the correct pronunciation of the word ‘scone’ to the hyperactive lifestyle of the royal family. The entire Oxford English Dictionary is split along party lines. The single exception to this universal tribalism was always the weather, which is why the weather has traditionally been the safest topic of conversation. Safety is key here. When you live in a tribal context such as this one, you never know who you might be speaking to, friend or foe, so the British devised their own version of “Halt, who goes there?” which amounts to pretending you are not the least bit curious about whether a friend or foe is in the vicinity. That way, you can behave as if we’re all friends.

Other parts of the world are not so fortunate when it comes to this kind of hypocrisy. I was often accused of being a hypocrite on my travels, but I shrugged the criticism off, like all valid criticism. Hypocrisy is an underestimated vice. In Papua New Guinea, for instance, people are no more tribal than us, but you seldom hear pointless conversations about the weather. This is surprising, since the weather there is remarkably similar to ours: incessant rain. Surely, you would think, this could provide ample scope for inconsequential exchanges of the kind that grease the wheels of social intercourse and keep Brits from tearing each other’s throats out with their bare teeth. But no, tragically the weather is a neglected topic over there, and the tribal disputes are becoming more deadly for two reasons: the arrival of guns, and the availability of cheap bootleg versions of Rambo. The latter have circulated widely in that rain-soaked land, though it’s a mystery how, given the almost total absence of video players.

Without our addiction to banal conversation and hypocrisy, and with readier access to guns and poorly-scripted action movies, we Britons would probably have gone the same way by now. As it is, there’s been plenty of loose talk of civil war, but exclusively among opinion writers. It’s counter-intuitive, yet over the past few years Brexit has taken the place of the weather as the polite topic of choice for placating strangers and alleviating the pregnant pauses of daily life. It has become the ultimate meaningless noise, the human equivalent of a humming fridge, so vacuous it makes Rambo sound articulate, and no one is obliged (or even allowed) to say anything substantive on the subject unless they are in the presence of members of the same tribe, which is never easy to determine as there are no agreed vetting procedures. We could, of course, wear badges like politicians, but it’s when you start parading your loyalties that the real trouble starts. Rosettes are not merely fashion death, like pink suits; they’re the actual root of all evil.

The only people (apart from politicians) rash enough to address the Brexit topic seriously, head on and in public, are members of the ever-expanding pundit tribe. Brexit has spawned a multitude of these. There is a pundit epidemic. It has gone on so long, this state of affairs, I would not be surprised to learn that some of them are the progeny of pundits, and that the pundits are actually breeding at a faster rate than the rest of us. No doubt procreation comes easily to them. After all, pundits can dispense entirely with chat-up lines and go straight into disquisitions on the precedents for proroguing parliament that require both interlocutors to stay together and, eventually, occupy the same bed if they have any hope of reaching some kind of satisfactory conclusion. I imagine they talk into the small hours before collapsing in exhaustion, then make love wordlessly at break of day. This would explain the slightly slept-in look of your average pundit.

Recently, I heard one such political pundit from the New Statesman – like all of his tribe, obsessed with the convolutions of Brexit – deliver an explanation of the current situation in a panel discussion. Clearly, this particular commentator’s reputation proceeded him, exactly like that of a garrulous drunk in the local pub. As a consequence, his fellow pundits seemed to recoil as he began, aware of the verbal carnage about to be unleashed.

They were not mistaken. The explanation was so complex, and became such gibberish after the initial half minute, I would have begged him to stop had I been on the panel, for fear of imminent mental collapse. As it is, on one of the few occasions I’ve knowingly chosen to keep tabs on the political scene, I had my trusty remote control in hand, index finger hovering over the mute button. The moment I realised he was a danger to himself and to civilised society, I gagged the bastard.

There’s no mute button for the demented climate, of course. Sadly, as soon as the pundit fell silent, I could hear again the dripping sound of the ongoing deluge. But I did at least derive some solace from being able, at will, simply by pointing a remote control with deadly accuracy, to render any pundit alive completely speechless. Better men than me have resorted to firearms for less.

Before I so rudely interrupted him, I managed to gather this much from the New Statesman’s man: that someone calling himself ‘prime minister’ had attempted to suspend parliament, then failed, then decided to secure a deal with the Irish (in a hotel on the Wirral favoured by newlyweds, though I may have made that bit up) and then, at the first hint of trouble from parliament, engineered a general election before the deal could be waved through by honourable members, and all because he had no election campaign if parliament obligingly waved it through, which it looked like doing. Now, I can’t swear, since I have developed a protective tendency for amnesia, but I think that’s the point where I pressed the mute button and the climate crisis, right on cue, resumed in all its fury.

If you will permit me to rewind to the proroguing of parliament that (according to the Supreme Court) never happened, it was around that time I really began to feel queasy about the man who we are laughably expected to call prime minister. The Boris dreams began, alternating with bouts of insomnia. I quickly acquired a slept-in look and my inner pundit began to gibber, inwardly. It was also around this time, I’m convinced, that I heard a previous employer of the man-now-calling-himself-prime-minister, one Max Hastings, reflect that England was going through its ‘Weimar phase’. It even felt that way for a moment, with the prospect of food shortages, riots, the total breakdown of social norms, until parliament passed the Benn Act to prevent us from crashing out of the European Union. Hang on, though… was that before or after the attempted proroguing? Who knows anymore? But, at some point, we had the unalloyed pleasure of hearing John Bercow, the Speaker, declare the prorogation ‘irregular’ and an example of government by fiat, then tell a member of the government who dared disagree that he didn’t give a ‘flying flamingo’ for his opinion.

Anyway, if this is our very own repeat of the Weimar period, a certain amount of auto-satire by the elite is in evidence, notably in the form of Rees-Mogg, the Leader of the House, who showed his contempt for the debate on the Benn Act by laying at full stretch across the front bench.

Actual satirists are humbled by the talent of such self-satirists, and maybe that is the crucial way in which England differs from Weimar: in Berlin at that time, there were grimly serious political monsters on the one hand, and then there were mocking cabaret artists. Here, in merry old England, it’s the parliament that provides the best jokes and no one would be seen dead watching cabaret. A television channel devoted to parliament, unimaginatively named the Parliament Channel, has drawn record audiences. Parliament is more popular than the average reality show. Along with his saucy line in flamingo euphemisms, the previous Speaker had a way of calling for order that made his face go red and his fans go weak at the knees. He was pantomime, cabaret, music hall and wordy Shakespeare rolled into one compact, overactive bundle. Little wonder, then, that honourable members, having been upstaged for the best part of a decade, made sure his replacement, Sir Lindsay Hoyle, had a voice more soporific than a cetacean’s. The Leader of the House need never be startled out of his beauty sleep again.

They once asked Peter Cook whether he thought satire had any political effect. “Absolutely,” he replied. “The greatest satire of the twentieth century was the Weimar cabaret, and they stopped Hitler in his tracks.” Now, with Cook long dead, one wonders if he grossly underestimated himself. Back then, you could puncture their pomposity, but our current lot aren’t nearly pompous enough. They’re just preposterous. Contemporary satirists (such as John Crace) feel they’ve been reduced to mere ‘transcribers’ by the greater satirical talents of those in power. Like the rest of us, there’s a growing sense that they, the professional satirists, have become the butt of the joke. In the British re-run of Germany in the thirties, the cabaret artists really have come out on top, only it’s Boris Johnson cavorting like Liza Minnelli.

The forthcoming election may well confirm the prediction of another German satirist: just like Bertolt Brecht accused the communist regime in 1953, our jocular rulers have decided to dismiss the people and appoint a new one. We got it right in 2016, of course, and it was ‘the will of the people’ (well, just over half of those who bothered to vote) to leave the European Union, but since then we, the people, have elected a zombie parliament which has thwarted our previous will. The solution could not be more obvious: the people’s will must be called upon to uphold what was the will of the people before the will of the people so rudely intervened. With this in mind, the people are being dismissed in order that a new one, which is actually the old one, can be appointed, only this time we shall have a soft-spoken Speaker and a proper majority Conservative government, so there’s no danger that the will of the people might be wrongly interpreted by a biased red-faced imp or thwarted by duly elected zombies.

What lessons can we possibly take away from all this? Well, firstly, there will be doctorates in it for future constitutional historians. Secondly, the will of the people is not always the people’s actual will. That’s why the European Union have a habit of asking the same question until they get the right answer. Oops, the less said about that, the better.

Suffice to say that we cannot be trusted as far as our own politicians can throw us, but aided by targeted advertising and a few suppressed reports on Russian interference, and abetted by concealing the fact that Dominic Cummings learnt everything he knows, even the thing about returning to the scene of the crime, from a character called Raskolnikov, the Great British electorate will finally get the correct answer and vote the best satirists back in with a thumping majority.

Except, of course, that will also be the wrong answer, since as a tribe the Great British electorate can be relied upon to mistake their best interests for the interests of the other tribe who, let’s face it, know far more than they do about their best interests. This is what Friedrich Engels, another well-known German satirist, described as ‘false consciousness’ and it has prevailed throughout the country’s short history of universal suffrage. The joke is always on the people. If you didn’t laugh, you’d cry.

But hey, let’s not get ahead of ourselves here. No spoilers. The election has only just been called, and it looks like being a real battle of wills… of the people. The big question is which of these two tribes will emerge the victor. My money is on the funniest tribe. Britons, like the readers of lonely-hearts ads, always reward a GSOH.

Which brings me, with almost uncanny circularity, back to Gauguin, that well-known joker and implicit colonialist. Here he is, anticipating by eighty years or more the naked piano player in Monty Python:

One thing I thought I knew for sure about Gauguin was that he lacked a sense of humour, but then I also thought, once upon a time, that politicians were serious people. What I do know is that Gauguin never visited these shores, so despite all his travels in the Caribbean and the Pacific in search of an escape from civilisation, he never encountered a tribe with two heads on their shoulders, or a land of two tribes with one will between them. He could have saved himself a lot of hassle. We were right here, a short ferry trip away.

Gauguin Portraits is at the National Gallery till 26 January 2020.

GLOSSARY

GSOH = a good sense of humour

Laconic: the word derives from a region of ancient Greece known as Laconia, which contained the city of Sparta. Its inhabitants had a reputation for verbal austerity and pith. The story goes that after invading southern Greece and receiving the submission of other key city states, Philip II of Macedonia turned his attention to Sparta and asked, menacingly, whether he should come as friend or foe. They replied “Neither.”

Losing patience, presumably with the protracted means of communication of the day as much as with the Spartans’ brevity, Philip sent another message:

“You are advised to submit without further delay, for if I bring my army into your land, I will destroy your farms, slay your people, and raze your city.”

This time, the Spartans sweetly replied: “If.”

Philip II never invaded Laconia, and nor did his son, Alexander the Great.