*” My father tried teaching me and my sister story writing while we were schoolchildren, but in the end, we chose different paths for ourselves.”

* “My father was a role model in manners, class, and humility.”

* “My father was nothing like Si-Sayed in our household, he was very kind and sympathetic to me and my sister.”

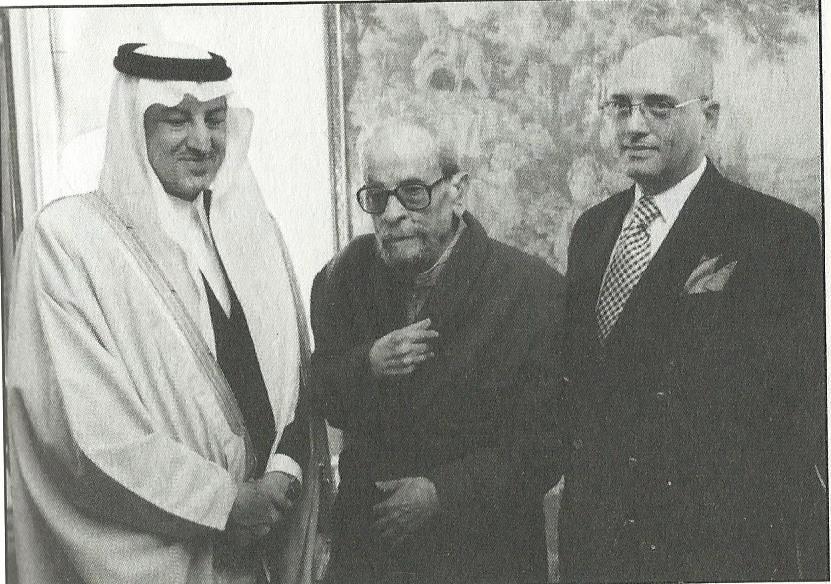

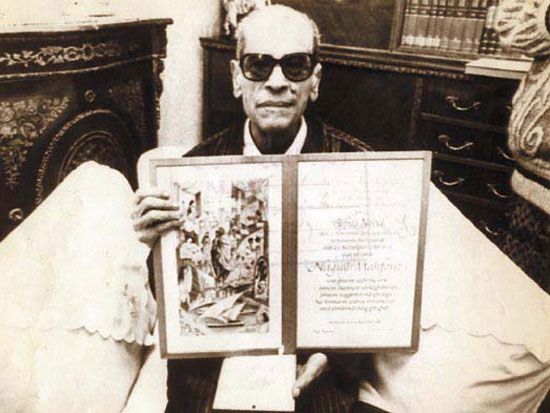

History will remember Naguib Mahfouz for being the first Egyptian and Arab author to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1988 and for his efforts in enriching Arab literature. His works include the Cairo Trilogy which consists of Palace Walk, Palace of Desire and Sugar Street. He is also known for The Thief and the Dogs, The Harafish, Miramar, Chitchat on the Nile, Al Madak Alley and Love on the Pyramid’s Plateau. Some of his works have been controversial, and by far Children of Geblawi has proven to be his most contentious novel. Many Azhar imams accused the novel of belittling religious figures and called for it to not be published. It was for that reason that there was an eight-year delay that prevented it from being fully published. In 1967, Lebanon’s Dar Al Adab published the novel, while it was banned in the author’s home country. Almost 40 years later, in 2006, Dar El Shorouk published the book on Egyptian soil for the first time. In spite of these setbacks, Mahfouz was able to publish this novel as a series of short stories in Al Ahram newspaper back in the 1950s.

Unfortunately, Mahfouz only gained more enemies after he won the Nobel Prize as he soon faced an assassination attempt when an extremist stabbed him in the neck. Though he survived, the attack had a lasting impact on his right hand which meant that he could no longer write. He also could not do his favorite activity after the attack, namely walking among the people in the street for an hour a day. Mahfouz’s works have also been made into various films and TV series, which only made him well known among the public rather than just Egypt’s intellectual and intelligentsia class.

Just recently, the Tkeit Abu el-Dahab building at the center of Fatimid Cairo has been renovated into a museum commemorating the Nobel Laurette. As the thirteenth anniversary of his death recently passed, Majalla had the pleasure to interview his daughter Hedy. In the interview, she expressed her desire that her father would be taught at schools all around the world, as she fears that he will be forgotten among the younger generations. She also spoke about the unfair libel her father endured during his lifetime, and also said that the person who attempted to kill him must not have read his literature. Furthermore, she revealed more about the tensions between the Mahfouz family and the American University in Cairo, which publishes his English translated books, and the fact that the family is seriously considering looking for an alternative publisher.

Q: Describe how you feel on the thirteenth anniversary of your father’s passing which coincided with the opening of the Mahfouz museum, something you have been waiting for a long time?

A: Of course, the opening of the museum has made this anniversary different and the fact that the opening happened during the lifetime of one of his family members has made this event even more special. While there are criticisms and observations on the museum, I am sure that they can be addressed, but the important thing is that it has finally come to the light of day.

Q: I feel that you’re not as thrilled as you could be with the grand opening. Did the long time it took to establish it cause you to lose interest in it?

A: I am happy with it, but I hope that Mr. Youssef El Akeed, its managing director, also makes it into a cultural center since it was planned to be both during its initial planning period.

Q: Do you feel that your father’s cultural and literary legacy is properly commemorated on an annual basis?

A: It differs year to year, some years his legacy is well honored and remembered and other years it is not. With the exception of the museum, this year’s anniversary of my father’s death has been met with silence and little commemoration.

Q: Why is that?

A: I couldn’t give a reason why.

Q: Do you ever fear that general interest in your father’s work will decline, something that has happened to other major authors in the past?

A: That is something I am afraid of since his works aren’t taught in schools. As you can see, English, French and German authors who have been dead for centuries are still remembered to this day because schools assign students to read their books. If my father and other authors don’t get the same treatment, then they might be forgotten by future generations.

Q: Are his works not taught at any school level?

A: I am speaking on the general scholastic sphere, I was told that he was part of academic curricula at one point, but has since then been removed. I also know that schools generally teach kids about the lives and general works of major authors, for example, I remember that I was taught about Shakespeare when I was at an American school.

Q: Do you want your father to be part of general school curricula?

A: Of course I do, and not just my father but all Arab and Egyptian authors. It is a tragedy that non-Arab authors are taught more in our schools and that Arabic literature is not an integral part of our school system. The only exception to this is “The Days” an autobiography by late Egyptian author Taha Hussien, which is taught in high schools.

Q: Do you think non-Arab audiences care more for father’s works more than Arab audiences?

A: The American University in Cairo (AUC) has always had good partnerships with Arabic authors such as my father, but recently it has focused mostly on publishing academic works rather than literary works and most authors it is currently contracted with write exclusively in English. Moreover, there are some differences that have arisen between my father’s estate and the University.

Q: Are those differences the reason why you stopped attending the annual Naguib Mahfouz award ceremony at AUC?

A: I have never spoken to the press on this topic and as a result, many unfounded rumors have been spread about it. I never intended on boycotting the ceremony, nor did I want to publically announce my non-attendance, but it all happened suddenly when a journalist said to me “I’ll see you tomorrow (at the ceremony)” and I said that I was, in fact, boycotting the university. And for the record, the Mahfouz family as a whole doesn’t attend that many events hosted by the university due to several disputes we have with the institution, which it has shown little interest in resolving.

Q: Have you considered contracting with a different publisher?

A: I have indeed thought of taking away publishing rights from the university, and I even filed three lawsuits against the institution. The university had two jobs with regards to my father’s works, first of all, it published and translated his novels and second it was contracted to act as an agent for his TV and film scripts. This agency contract should have ended once my father passed away, but it continued to sell the rights to his scripts and it also got involved in the publishing rights of his Arabic work, which it doesn’t have any rights in. Legally, an agent does not own the works it is representing; rather it should only provide a service to the owner of the text.

Q: Do you feel any resentment towards those who treat your family differently after your father’s passing?

A: Thankfully, my close friends never abandoned me after my father’s passing, but there were acquaintances that never gave me the time of day since his death. I keep those friends close to me and choose to not think about the others since I do not like those who only befriended me to get close to my father.

Q: My question was geared more towards institutions, such as AUC.

A: Unfortunately, our family isn’t the only one that has grievances with AUC. I read in Akhbar El Adab newspaper, that Mr. Bahaa Taher also has his own conflicts with the institution. AUC has treated my family in such a conceited manner despite the fact that my father won the Nobel Prize before his agreement with the university since other publishers were translating his work into English and the Nobel Prize committee read these pre-AUC translations. I understand that the university has a vast history, but it has no right to do this to us because we had a mutually beneficial agreement.

Q: Do you have any dreams you wish to fulfill?

A: As I said, I wish that my father and his fiction would be taught in schools the same way non-Arab authors are taught in schools. I also wish that more people truly understood what my father was trying to convey in his books since he was unjustly misrepresented and his use of symbolism was gravely misunderstood. He was even faced with an assassination attempt from an ignorant person who never read his works.

Q: How can your father’s public image be ameliorated in your opinion?

A: By having his work taught in schools. The reason being that classes allow students to deeply delve into these literary texts, thus they tend to read books differently than most other readers.

Q: Do you think the cinema industry has embellished your father’s work?

A: My father always participated in the scriptwriting process, since he knew that the cinema industry tends to change the source material to make it more appealing to general audiences. He always told me that anyone who wanted to judge his writing needed to do so through his novels, rather than his films.

Q: Which film did your father think changed the least from the original source material?

A: I never asked him, but I think many of the films based on his works were badly made. I remember once he read me and my sister a speech from one of his critics, said critic called my father a “belly dancer enthusiast”. The critic was mostly referring to the film adaptation of the Cairo Trilogy which focused heavily on the bellydancer plot from the books. Naturally, anyone who sees the film without reading the novels would think that the books are about the history of belly dancing in Egypt, but as I said reading the original source material is critical before making judgments.

Q: Did your father object to how the Cairo Trilogy was presented on film?

A: I don’t think he had any reservations to how Hassan El Imam directed the film.

Q: Was your father democratic, or was he similar to the patriarchal Si-Sayed character from the Cairo Trilogy?

A: Si-Sayed was actually based on his own father, but he also told me that the art of novel writing depended on both reality and fictionalization, as such he used creative liberties to create his characters. And to answer your question, my father was nothing like Si-Sayed in our household, he was very kind and sympathetic to me and my sister and my mother would often tell him that he’s spoiling us. He also wanted to teach us how to write so we could follow in his footsteps. So how could he be SI-Sayed if he wanted us to be as successful as he was?

Q: Did your father’s fame benefit you or hurt you in the long run?

A: I did not exploit my father’s fame in any way, for instance, I got my job at an American company through my hard work and neither through my connections nor my relation to my father.

Q: I meant your psychological wellbeing; sometimes having a famous parent can be a psychological burden on a person, so did you ever feel any pressure for being Mahfouz’s daughter?

A: As a family, we stayed away from the limelight and we were comfortable with such arrangements. Even today, I am not comfortable with making media appearances and the interviews I give are few and far between. Even when I appeared on TV, I had the precondition that the interview would be prerecorded rather than live since I am not used to it.

Q: Did your father insist on your family staying away from the limelight?

A: No, it was entirely our choice.

Q: Did he allow you to meet his houseguests?

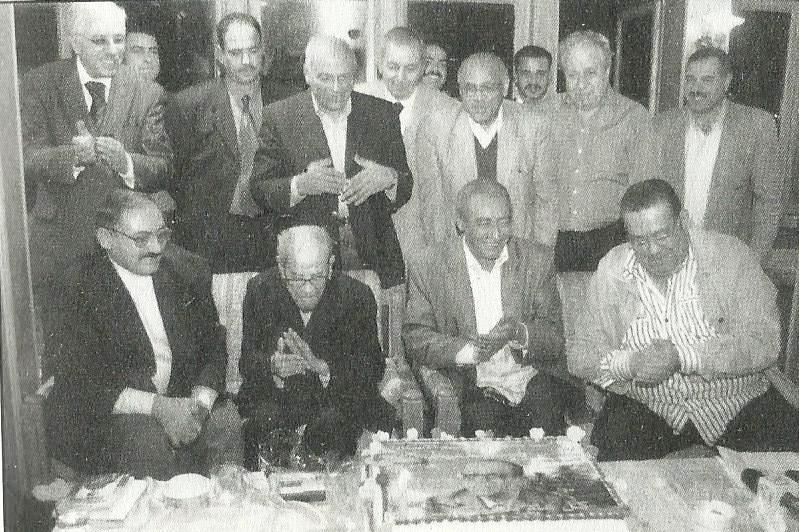

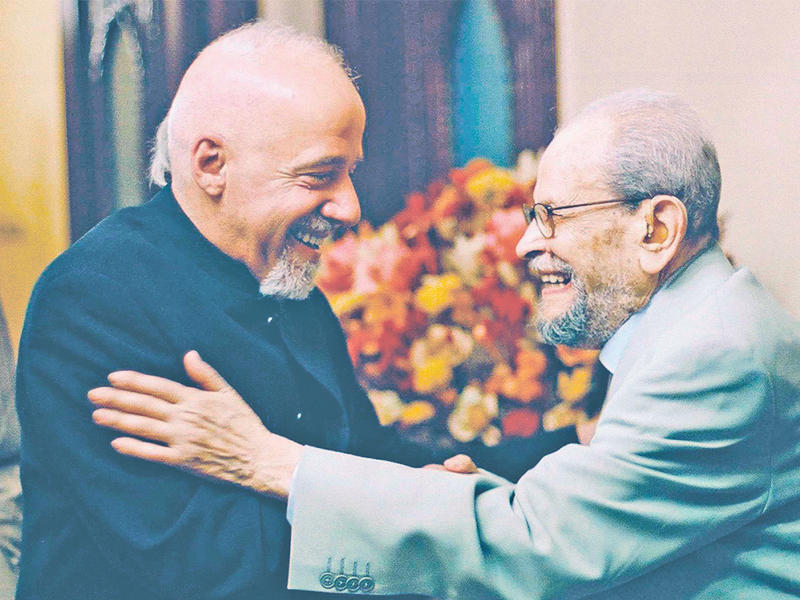

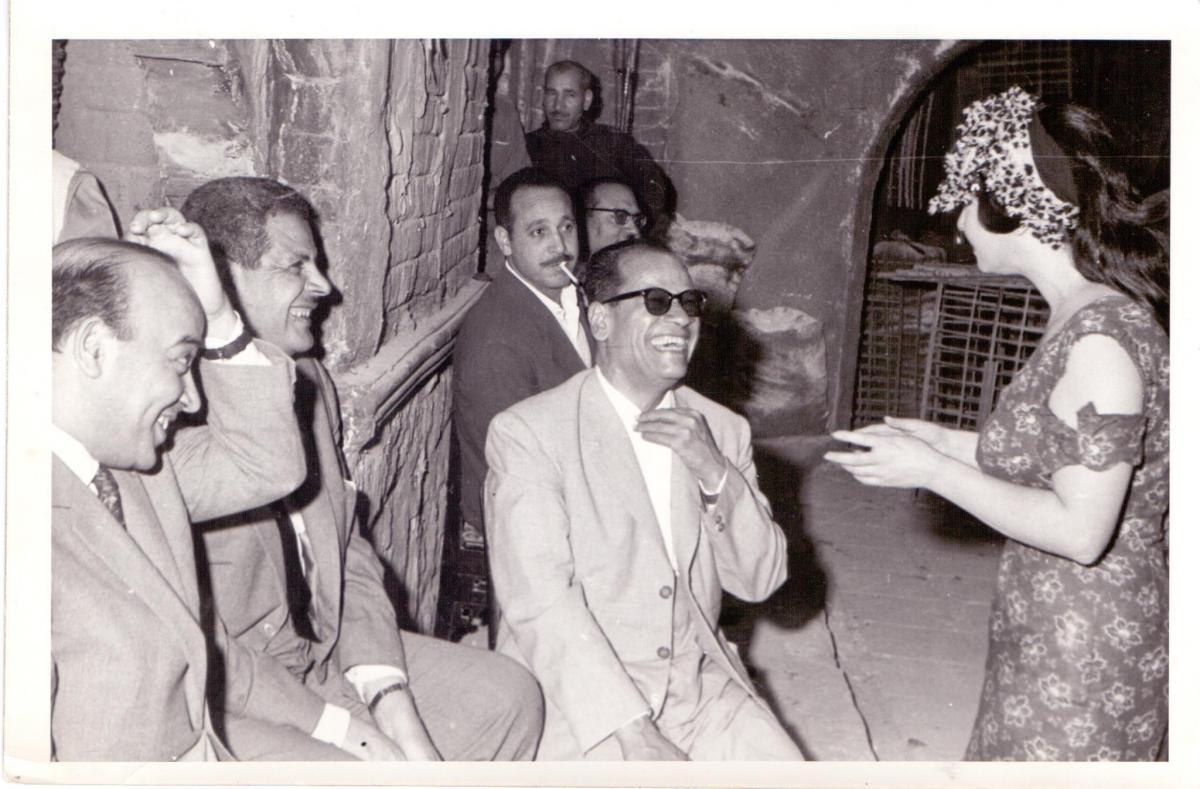

A: I remember that my father often had guests over and he would have no problem with us speaking to them, for example, I remember “Uncle” Tharwat Abaza and Tawfiq El Hakim would often visit my father. We would love having them over as they were his best friends. However, I don’t recall my father’s students frequently coming over to our house, as he often met them at a public place like a café.

Q: What do you miss most about your father?

A: I miss everything he used to teach me, as he was an absolute gentleman when it came to how he treated others. He was a role model in manners, class, and humility.

Q: Did he have any final wishes for you before his passing?

A: He didn’t have any final wishes for us per se, but throughout his life he wanted either my sister or me to follow in his footsteps and become a novelist. He tried teaching us story writing while we were schoolchildren, but in the end, we chose different paths for ourselves.

Q: What would you like to accomplish by next year’s anniversary?

A: I want to dedicate a section in the museum to the Harafish group, who were among my father’s closest friends. I would also like to exert more effort in ameliorating my father’s reputation.