Time plays cruel tricks on us all, but few could have imagined that Brexit, having tricked a nation into self-inflicted harm, would end by playing one of its cruellest tricks on our beloved monarch. Queen Elizabeth II might be forgiven for thinking that her time is up and that her long reign is being rounded off, tragedy-to-farce style, with a conventional narrative device of the bookend scene, just so we (her subjects) can have the satisfaction of a neat ending.

Why else, after such a long career of public service, would a woman whose first prime minister was Winston Churchill end up with his impersonator? Not a very good impersonator, to be sure. It’s true he hunches his shoulders in the same way as the great man used to do, as he bull-doggedly surveyed the smouldering ruins of yet another blitzed neighbourhood, but where’s the cigar, and what’s with the blond wig? He’s a Churchill soundalike who, however grand his diction, could never be mistaken for the great man’s love child, or should that be the great man’s great grand love child? His actual ancestors were on the wrong side at Gallipoli. The Queen must think this is some weird prank that history has devised for her alone, a massive hint that she really ought to have abdicated by now.

If she does, then she greatly underestimates the prankster; she is far from being the only victim of history’s little joke. This week, it was the turn of the inhabitants of Newport in Wales. The Prank Minister showed up, with his trademark stoop and blond wig, and immediately descended on a local poultry farm for a photo opportunity involving a bird of (as my father used to say) the feathered variety. He is so besotted with his own Churchillian pose, this Prankster-in-Chief, that having grabbed an unfortunate hen he could not resist muttering “Some chicken...” under his breath, though in a rare instance of self-restraint he did not finish the quote.

For those who haven’t recently written a biography of Churchill, let me remind you that the war leader was in Ottawa at the time. The year was 1942, and he was describing the conduct of the French:

But their generals misled them. When I warned them that Britain would fight on alone whatever they did, their generals told their Prime Minister and his divided Cabinet, “In three weeks England will have her neck wrung like a chicken.” Some chicken! [Applause] Some neck! [Applause]

And so, fast forward to a Welsh chicken in the summer of 2019. If race memory had told it what Sir Oswald Moseley, our very own black-shirted populist, used to do to chickens – he strangled them for amusement – the Welsh chicken wasn’t letting on. It remained perfectly composed.

We are all in the same remarkable state of calm as that bird. You could threaten to chlorinate us and we would not flinch. In the midst of peacetime, we, like the blameless folk of Newport, are being threatened with a wartime economy by a smiling Churchill impersonator who looks and sounds nothing like the original, apart from a bad stoop. It’s the revenge of the famous English sense of humour, and only that same sense of humour will ever get us through the horrors to come.

All this would be far more distressing if it were not for a certain psychological mechanism to which recent political events have forced me to resort. I have yet to accept that Boris Johnson is Prime Minister. Whenever news anchors say ‘the Prime Minister told reporters’ or ‘Today, the Prime Minister visited,’ my rational mind assures me they are referring to no one in particular, but to a phantom. I simply have not admitted to myself that this dodgy individual has risen to the post of Her Majesty’s First Lord of the Treasury. If the times appear pregnant with possibility, this is undoubtedly a phantom pregnancy. There can be no war in peacetime, I tell myself. The people of Great Britain will not tolerate the proroguing of parliament by an unelected Etonian numpty. Theresa May has left office in order to pursue her hobby of dancing at cricket matches, but she has not been replaced by a scoundrel with a bust of Pericles on his desk who has promised a golden age and sacrificed his money-making ventures to the service of a grateful nation. No man who embodies the phrase “rewards for failure” – having been richly rewarded for a whole string of bad decisions and even worse articles that have lowered, if such a thing were possible, the standards of British journalism – has taken up residence there, nor has he achieved his lifelong ambition. That glum little dwelling in Downing Street has no such occupant, or his live-in girlfriend, just a cat named Larry with his own sardonic Twitter account.

I admit this may not be a mental trick available to the Queen. She, after all, has to meet the new premier in the flesh. But it has so far insulated me against the unbearable reality that a party of humourless pranksters, not to be outdone by the Italians, or by the desperate citizens of Ukraine, has elevated a comedian – sorry, an Etonian – to the most important position in the land. I simply have not registered that we have a numpty in Number Ten.

NEWSPEAK

Curiously, despite being old Etonians and prognosticators, neither Aldous Huxley nor George Orwell predicted this comic turn of events: that a boy from their school would one day represent the apotheosis, and at the same time the Nemesis, of their country’s famously dark sense of humour.

This may not be surprising. While Huxley wrote with a certain amount of archness and wit, Orwell lacked these qualities almost to the point of renunciation. His muse was an austere one, rather like the love interest in his most celebrated novel, Julia, of whom more anon. Nineteen Eighty-Four is a dystopia so unremittingly grim that any humour belongs to the underclass, the ‘proles,’ rather than to the elite of party members. Its hero, Winston Smith, may well have been named after Churchill, but he has none of his namesake’s humour, nor his facility with words. His diary entries are atrociously written, as if by a virtual illiterate. He may have a residual dream of the Golden Country and wake with the word Shakespeare on his lips, but Winston is already a long way into the indoctrination that will finally claim him. We are not told this explicitly, but he may well be the last of his kind, a doomed remnant of freedom in the totalitarian system of Oceania or, as England is now known, Airstrip One. Orwell toyed with the idea of a different title before his publisher dissuaded him: it was to be called The Last Man in Europe.

The novel is definitely of its time. There are bombed streets of the kind Keith Richards remembers playing in. There are shortages of everything, and people smoke bad cigarettes washed down with Victory gin, which makes you gag. There are some uncanny premonitions, such as this from Winston’s diary:

Last night to the flicks. All war films. One very good one of a ship full of refugees being bombed somewhere in the Mediterranean (p. 11).

But the startling currency of this is deceptive. Comparing Nineteen Eighty-Four with Brave New World, it is immediately obvious that Orwell’s old tutor has the better claim to prophetic powers. Perhaps North Korea is the only place where people would look at this future and think “Wow, now that’s uncanny!”

Nonetheless, the pupil displays little deference towards his former tutor. He puts these words in the mouth of his most sinister character, O’Brien:

…the world we are creating? It is the exact opposite of the stupid hedonistic Utopias that the old reformers imagined (p. 306)

This isn’t just a claim to clearer foresight on Orwell’s part; it’s also a sally of literary criticism. It was Wells who had predicted the brightest futures, made possible by advances in science, and Huxley who had added the ingredient of hedonism, turning dystopia into a vision of our present – at least the present occupied by the super-rich, with their private jets to ferry them from one party in Ibiza to another in Mykonos. Orwell (using O’Brien as mouthpiece) seems to be saying that is all far too hi-tech, because he struggles to see beyond the immediate circumstances of ration books and squalor.

But perhaps it’s unfair to expect prophecy of Orwell in the first place. He was really engaged in a thought experiment: ‘What if totalitarian communism of the type that has taken hold in Stalin’s Russia and has since swept over half of post-war Europe, came here?’

Ingsoc is the result, or English Socialism. The entire point of this future society is the control of people to the point of reading and dictating their thoughts. The party goes to absurd lengths to suppress aberrant thinking, even placing microphones in the country lanes to detect lapses into unorthodoxy. The Thought Police exist to enforce this. Thoughtcrime is the most serious offence. Through Newspeak, the Party are reducing language to a functional simplicity that will one day have the effect of preventing rebellious thought altogether.

Orwell was convinced that the ability to think subversive thoughts was dependent on the language in which to think them. In ‘Politics and the English Language’ he saw the various defects of modern English as amounting already to the destruction of thought in a time of dictatorships. You could guard against the laziness of hackneyed phrases, passive voice, circumlocutions and the like, or else you could let

…the ready-made phrases come crowding in. They will construct your sentences for you – even think your thoughts for you, to a certain extent – and at need they will perform the important service of partially concealing your meaning even from yourself. It is at this point that the special connection between politics and the debasement of language becomes clear [my italics].

To a certain extent. By 1984, that extent will be edging towards total.

Orwell also notices the impoverishment of the modern idiom. He takes a passage from the King James Bible, a translation of Ecclesiastes:

I returned and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all.

The language of this passage is timeless and beautiful, yet idiosyncratic and slightly quaint. Orwell then modernises it thus:

Objective considerations of contemporary phenomena compel the conclusion that success or failure in competitive activities exhibits no tendency to be commensurate with innate capacity, but that a considerable element of the unpredictable must invariably be taken into account.

There are still plenty of people speaking like this – and worse – from our civil servants to people in public relations and marketing.

In Nineteen Eighty-Four, a future that has yet to happen, this process of decline has been hastened by the party in a conscious effort to destroy thought. Rather than encountering a rat in his personal Room 101, as his hero does, Orwell would more probably have encountered a copy of the Newspeak dictionary. The character of Syme illustrates the process. A zealot of the new language, though this doesn’t save him from the fate of being ‘vaporised’ later, Syme is working on the definitive Eleventh Edition of the dictionary. Even in the work canteen his enthusiasm for the project means he can speak of little else.

We’re getting the language into its final shape… You think, I dare say, that our chief job is inventing new words. But not a bit of it! We’re destroying words – scores of them, hundreds of them every day…

It’s analogous to the degradation of the environment.

It’s a beautiful thing, the destruction of words. Of course, the great wastage is in the verbs and adjectives, but there are hundreds of nouns that can be got rid of as well. It isn’t only synonyms, there are also the antonyms... A word contains its opposite in itself. Take “good” for instance. If you have a word like “good”, what need is there for a word like “bad”? (p. 58)

(If you have a word like woke, what need is there for a word like awoken? If you have a phrase like ‘my bad’, what need is there for a phrase like ‘sorry’?)

“Ungood” will do just as well – better, because it’s an exact opposite, which the other is not. Or again, if you want a stronger version of “good”, what sense is there in a whole string of vague useless words like “excellent” and “splendid” and all the rest of them? “Plusgood” covers the meaning; or “doubleplusgood” if you want something stronger still… the whole aim of Newspeak is to narrow the range of thought. In the end we shall make thoughtcrime literally impossible, because there will be no words in which to express it. Every concept that can ever be needed will be expressed by exactly one word, with its meaning rigidly defined and all its subsidiary meanings rubbed out and forgotten.

Syme then goes on to describe the new dawn when there will be Newspeak versions of ‘Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, Byron’. Mercifully, Orwell spares us these bowdlerisations.

BACK TO (RE)SCHOOL

The effects of his prep school may have been the most damaging on Orwell’s mind. In ‘Such, Such Were the Joys’ he describes how ‘to survive, or at least to preserve any kind of independence, was essentially criminal’ and that he lived in a world ‘where it was not possible to be good.’ In this extended autobiographical account, he even uses a phrase that prefigures the famous boot stamping on a human face that O’Brien offers Winston as a vision of the future:

Virtue consisted in winning: it consisted in being bigger, stronger, handsomer, richer, more popular, more elegant, more unscrupulous than other people—in dominating them, bullying them, making them suffer pain, making them look foolish, getting the better of them in every way. Life was hierarchical and whatever happened was right. There were the strong, who deserved to win and always did win, and there were the weak, who deserved to lose and always did lose, everlastingly.

What he calls winning here is what O’Brien will refer to as power, and that power is an end in itself. It is achieved by domination. O’Brien is like the headmaster in a school devoted to the destruction of knowledge, a kind of anti-school where pupils’ minds are emptied rather than filled, their critical powers are blunted rather than sharpened, and where the three most important principles (as Tony Blair did not say) are re-education, re-education and re-education.

Could it be that, along with the satire on socialism, Orwell was having a go at the power structures of education? In ‘Such, Such’ he wonders whether, even in more modern times, without ‘God, Latin, the cane, class distinctions and sexual taboos,’ it might still be normal for schoolchildren to ‘live for years amid irrational terrors and lunatic misunderstandings.’ Schools may change, but schooling will go on.

Eton was to leave fewer scars than the prep school. There is a story that in order to deal with a bully, he and a fellow pupil resorted to the dark arts:

The late Sir Steven Runciman, the medieval historian, revealed in a letter written shortly before his death that he and Orwell practised black magic on a wax effigy of Philip Yorke, an older boy who had been threatening and offensive.

They were horrified, however, when Yorke first broke his leg and then, months later, developed leukaemia and died (Daily Telegraph, 18 May 2003).

If Orwell was left feeling guilty ever after, it was for having toppled, and even perhaps slain, a bully. There are worse things to feel guilty about.

Though it might not have been pervaded by the same smell of boiled cabbage as St Cyprian’s, Eton was a hard environment for a naturally independent-minded lover of justice. The tradition of ‘fagging’ was still current in his time there, whereby sixth formers got younger boys to fag for them. Their services might include warming the toilet seat in the winter, on pain of having their heads shoved through it. The phrase beloved by politicians to this day of ‘holding someone’s feet to the fire’ derives from the same ethos, and was taken quite literally as a way of punishing boys or extracting information from them.

We do not know much about Orwell’s period (as Eric Blair) at Eton, but there is something very reminiscent of school about the conditions in his great novel. ‘Doubleplusgood’, for example, has an undeniable ring of the school report about it, the experience of being constantly assessed and compared. In fact, the whole of Oceania is like one massive school where it is required forever to be on one’s best behaviour. It is even known as a ‘facecrime’ to allow a discontented expression to pass, however fleetingly, across one’s features. Every move, every word is monitored. Even at home, the telescreen’s eyes and ears are virtually inescapable; in order for Winston to write his diary, he has to hunker down in a concealed corner of his room away from the surveillance. In the next door flat, it is the children who do the spying – on their own parents. The flat reeks of the same boiled cabbage that hangs like a pall over the novelist’s memories of St Cyprian’s, his old prep school.

Winston’s workplace, the Records Department in the Ministry of Truth (known in Newspeak as Minitrue), is still more oppressive. None of his fellow toilers in this vineyard can be trusted. The canteen, the scene of Winston’s conversation with Syme, resembles a school dining hall – not of Eton College necessarily, but almost certainly of the prep school that inspired Orwell’s greater loathing.

It was Huxley, a fellow Etonian, who picked up on the sadism in the book. He complained that it was inefficient and would not last. The sadism of a school, however – and a boys’ school at that – has an efficiency all of its own. It is designed to reward endurance. By sticking at it long enough a boy can eventually replace his masters and gain the privileges of the older boy. This all happens within the relatively small compass of six years, with every boy progressing from despised new boy to respected bully. It is a hierarchy that is mirrored in the inner and outer party of the novel, with the proles beneath and kept out of the hierarchy without hope of advancement. This school system is surely the key to an otherwise mysterious aspect of Nineteen Eighty-Four: its seemingly unmotivated violence. Sadism is all very well, but is it an end in itself when transferred onto the level of an entire society?

The explanations O’Brien gives to Winston (under intense torture) suffer from a murderous circularity: the party seeks to control the individual, yet to do so the individual has to be eliminated. No individual sadist enjoys this process. It is even difficult to imagine Big Brother enjoying it. The subject of the sadism here is the party itself. To remove sadism from the personal dimension in this way, to make it impersonal, is a little bit like the line traditionally used by headmasters before they administered corporal punishment: This is going to hurt me more than it hurts you!

In this manner, the individual sadist is transformed into a functionary of a higher sadism and becomes the masochist. This is precisely the tone of O’Brien in the grim scenes where he finally has Winston in his care. He sounds like the disappointed head teacher when Winston fails to come up with the right answer. The torture is really a violent form of examination and assessment that is necessary to turn the raw material of the errant boy into a proper member of the party, but the process of physical violence necessary to achieve this transformation is no source of pleasure to O’Brien – he is capable only of disappointment. Oh dear, one can almost hear him thinking, you’ve gone and let yourself down again, old chap.

REBEL REBEL

Rebel rebel, you've torn your dress

Rebel rebel, your face is a mess

Rebel rebel, how could they know,

Hot tramp, I love you so?

(David Bowie)

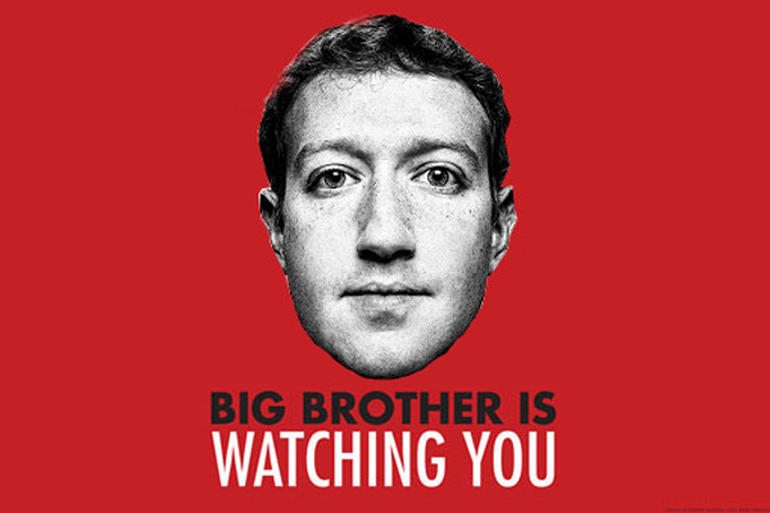

On the very first page we are introduced to the presiding genius of the novel, the ubiquitous Big Brother:

The hallway smelt of boiled cabbage and old rag mats. At one end of it a coloured poster, too large for indoor display, had been tacked to the wall. It depicted simply an enormous face, more than a metre wide: the face of a man of about forty-five, with a heavy black moustache and ruggedly handsome features.

Compare this with the moment on page 20 when Winston’s eyes meet O’Brien’s across a crowded canteen; it also has a hint of homoeroticism:

Momentarily he caught O’Brien’s eye. O’Brien had stood up. He had taken off his spectacles and was in the act of resettling them on his nose with his characteristic gesture. But there was a fraction of a second when their eyes met, and for as long as it took to happen Winston knew – yes, he knew! – that O’Brien was thinking the same thing as himself.

What Winston does and doesn’t know is one of the threads going through the book. We find later that he knew all along that O’Brien was his mortal enemy. In fact, the relationship with O’Brien is a case of sustained doublethink, since Winston both knows and doesn’t know that O’Brien is not his accomplice and fellow rebel. O’Brien, for his part, has a clairvoyant, quasi-supernatural ability to read Winston’s thoughts, the difference being that he does so without illusion. Is O’Brien a double-thinker? It’s impossible to say for sure. Later we have this description:

O’Brien was a large, burly man with a thick neck and a coarse, humorous, brutal face. In spite of his formidable appearance he had a certain charm of manner.

At this point Winston can only hope that O’Brien is an ally, a man who harbours equally unorthodox thoughts, and yet the eventual discovery that this is far from the case seems hardly to matter. By the end of his savagely painful re-education, far from hating O’Brien for administering the pain, Winston has a ‘deep love’ for him.

In contrast we know from early on that Winston ‘disliked nearly all women.’ He has a particular dislike, the kind we would now associate with an ‘incel’, for one woman in particular, the one who will eventually become his lover:

Vivid, beautiful hallucinations flashed through his mind. He would flog her to death with a rubber truncheon. He would tie her naked to a stake and shoot her full of arrows like Saint Sebastian. He would ravish her and cut her throat at the moment of climax.

Like Saint Sebastian, notice; i.e. like a helpless, naked man writhing in a loincloth.

It is obviously contagious, this society’s hatred; these ‘hallucinations’ come while the assembled group are engrossed in the Two Minutes Hate. Yet maybe the only relief from the novel’s gloom comes in the shape of Julia, who finds a way to approach Winston and who turns out to be his only kindred spirit, a real rebel. “I’m corrupt to the bones” she tells him before they first have sex. She helps him dodge the microphones and the telescreens, but there is little of the intellectual in her rebellion. “You’re only a rebel from the waist downwards,” he tells her. When he reads from the forbidden book, passed to him by a supposed member of the resistance, it explains the world order from the perspective of the party’s history and ideology. Julia, however, falls asleep. In a sense, so does the reader. How cute of Orwell that he was unaware how bad it looked when his liveliest character found THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF OLIGARCHICAL COLLECTIVISM soporific.

It is up to O’Brien to interrupt the lovers’ idyll, but for a while after his imprisonment in the Ministry of Love, Winston preserves his illusions about him. At last they are shattered when O’Brien walks into his cell:

The boots were approaching again. The door opened. O’Brien came in.

Winston started to his feet. The shock of the sight had driven all caution out of him. For the first time in many years he forgot the presence of the telescreen.

‘They’ve got you too!’ he cried.

‘They got me a long time ago,’ said O’Brien with a mild, almost regretful irony. He stepped aside. From behind him there emerged a broad-chested guard with a long black truncheon in his hand.

‘You knew this, Winston,’ said O’Brien. ‘Don’t deceive yourself. You did know it – you have always known it.’

Yes, he saw now, he had always known it.

By the time O’Brien has finished with him, he will be a wreck of a man, prematurely aged and almost dead. Then he will hear about the future being the foot stamping on a human face – forever. He will also, incidentally, learn from his Inner Party tutor that “We shall abolish the orgasm.”

Love is against the rules. Winston will only pass the exam when he wishes the torment of a face-eating rat on Julia, rather than on himself. Yet there is something akin to love between himself and O’Brien. This is a school for boys, after all.

I’VE SEEN THE FUTURE, BROTHER: IT IS MURDER

Give me back my broken night,

My mirrored room, my secret life,

It’s lonely here, there’s no one left to torture…

(Leonard Cohen, ‘The Future’)

It’s curious that the most famous of all dystopian visions should be neither especially accurate as a prophecy, always assuming one is not living in North Korea, and actually an account of the author’s schooldays. Yet, just as ‘Such, Such Were the Joys’ was about as joyful as Joy Division, and just as it was criticised for being an exaggeration of the conditions in a prep school near Bournemouth, so Nineteen Eighty-Four has barely a glimmer of joy in all its pages and some readers have found its regime implausibly brutal. Huxley was one such reader. He felt the sadism was unsustainable. To be fair, so does Winston: ‘It is impossible to found a civilisation on fear and hatred and cruelty,’ he tells O’Brien. ‘It would never endure.’ When asked what will stop it enduring, Winston invokes the Spirit of Man. ‘And do you consider yourself a man?’ asks O’Brien, to which his student replies that he does. ‘If you are a man, Winston, you are the last man.’ It is a relic of the novel’s original title.

The last man is destined for death or infantility. In a strange way, Huxley and Orwell might have agreed on this point. But there is no sense in Huxley’s utopian dystopia that this end will be accomplished by torture, perhaps because he had discovered the perfect infantilism of desire. Just when men and women think they are leaving childhood behind, they are merely swapping one kind of childishness for another. The oppression of childhood and the hierarchies of school come back to haunt the bedroom. This much is harmless between the consenting amateurs of infantilism.

One’s schooldays, too, are safely behind one, you would think. Yet you learn something new every day. Reverse that dictum and you have the horror of second boyhood, the order of events reversed, and the certain prospect of unlearning something every day, helped in this rubbing out of experience by the anti-tutors of ideology. The future is a return to school – to be unschooled.

When people make the effort to see the future, they may be forgiven for actually seeing the past. How else can one be expected to imagine the coming horror?

In a song called simply ‘The Future’, Leonard Cohen tells us he’s seen the future, brother, and it is murder. Yet the things he sees are familiar horrors from his own youth. He sees lousy little poets coming round ‘trying to sounds like Charlie Manson’. He sees fires in the road. In the guise of the ‘little Jew who wrote the Bible’ he sees nations rise and fall. And as things slide out of control, he sees ‘your woman hanging upside down, her features covered by her fallen gown’. It’s a vague recollection of the corpse of Mussolini’s mistress, Claretta Petacci, hanging from a meat hook after her summary execution. There had been no trial. Some people would call that murder.

There’s no real mystery about the future. So long as you think it will be a new golden age, then you are speaking the glib language of the numpty in Number Ten who likes to keep a bust of Pericles on his desk and imagine that the greatest country on earth will be his legacy.

If, on the other hand, you think the future will not be so good – if, in fact, you’re almost certain it will be doubleplusungood – then it will resemble that thing you fear more than anything, the worst thing in the world, and for George Orwell, the artist formerly known as prep school pupil Eric Blair and as an Etonian, not a comedian, that worst thing was school.

FOOTNOTE: DAVID BOWIE AND NINETEEN EIGHTY-FOUR

The song ‘Rebel Rebel’ may have neatly encapsulated Julia’s sexiness and her defiance of the rules. However, it is well known that Bowie was unable to persuade Orwell’s widow, Sonia, to agree to a musical based on Nineteen Eighty-Four. Bowie was furious. “For a person who married a socialist with communist leanings, she was the biggest upper-class snob I’ve ever met in my life,” he told Circus writer Ben Edmonds. “‘Good heavens, put it to music?’ It really was like that.” But was it really snobbery? ‘Doubtless, Sonia did hate the idea,’ says Dorian Lynskey,

but then she had approved almost no adaptations in any medium since the fiasco of the 1956 movie and she certainly didn’t meet Bowie, so that anecdote can be taken with a pinch of salt. It’s debatable whether a hypermodern, hedonistic, bisexual rock star would have had better luck with a 70-year-old Orwell (The Guardian, 19 May 2019).

We shall never know. There are those who have called Orwell a Tory anarchist rather than a socialist, and he was certainly socially conservative, but it seems unlikely he was ever a snob.

Sonia, on the other hand, was free spirit enough to hang out with some pretty anarchic personalities. After Orwell’s death, she went on to have affairs with painters, including Lucian Freud, and with a French philosopher. She was also friends with Bacon and Picasso. Maybe she just didn’t rate David Bowie.