Over 68.5 million people have been forcefully displaced worldwide as a result of persecution, conflict, violence or human rights violations. Close to 40 percent originate from the Arab region which continues to pose overwhelming challenges, with multiple and complex emergency situations on an unprecedented scale. The humanitarian and refugee crisis in Syria remains the largest in the world after more than 8 years of conflict. More than 5.6 million have fled the country as refugees, and another 6.2 million people are displaced within Syria. Elsewhere, violence and instability in countries such as Iraq, Libya and Yemen have triggered waves of displacement. A tragic by-product of ongoing conflicts in the region that has a disproportionately young population with over 50 per cent under 18, is what many are calling a “lost generation” of unschooled, psychologically traumatised children. Carsten Hansen, Middle East Regional Director at the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), told Majalla that there is a “very clear and present danger of losing an entire generation of children wherever there is conflict - be it Syria, Yemen, Palestine, Iraq or elsewhere.”

Children are born into situations beyond their control, yet they bear the brunt of war, destruction, displacement, and social and economic turmoil, and they will continue to pay the price for these conflicts. The long-term impacts on the future of the region's youth who may not remember a time before brutal war, and thus the region itself, are huge, devastating and unpredictable.

THE TRAUMA OF WAR

Less talked about than physical and social issues, mental health problems are extremely widespread in refugee populations. According to a report by the German Federal Chamber of Psychotherapists, more than half the number of refugees from war zones suffer from some kind of mental illness. Many children caught up in war have been orphaned, seen their homes and communities destroyed, and are starved of food and water, education, medical treatment – deprived of their most basic human rights. According to Unicef, children are often exploited, abused, forced into armed groups or early marriage. The depression, PTSD, suicidal tendencies, severe aggression and other mental illnesses that result from these horrors are invisible wounds that are not being detected early enough, let alone treated efficiently, in Syria and beyond, as this quote from a teacher in the Syrian town of Madaya, in Save The Children’s March 2017 report, Invisible Wounds, makes clear: “The children are psychologically crushed and tired. When we do activities like singing with them, they don’t respond at all…they draw images of children being butchered in the war, or tanks, or the siege and lack of food.”

Medics treating the children in these war-torn countries say the devastation and lasting mental health implications far exceed anything they have seen before and the symptoms eclipse those of PTSD. Dr. M.K. Hamza, a neuropsychologist with the Syrian-American Medical Society (SAMS), created the term ‘human devastation syndrome’ because he felt any existing terms are not adequate to accurately describe the levels of horror experienced by these children.

NRC’s Hansen told Majalla that the psychological scars of conflicts can be seen even after the conflict ends and in areas where escalations in fighting keep happening, children are subjected to repeated traumatic violence that can undermine years of work.

“Just in the Gaza Strip, for example, we found that 68 per cent of children living close to the Israeli perimeter fence have clear indications of psychosocial distress, many of whom witness explosions in their neighbourhood. They experience unusually high rates of nightmares and suffer concentrating at school,” said Hansen.

Nevertheless, Hansen expressed that there is reason for optimism. “But we’re also encouraged by very positive results – children who get the chance to deal with their psychosocial distress professionally have a high rate of success.”

The child survivors face bleak futures if immediate, targeted and long-term assistance is not given to provide the mental health and psychosocial support that they need, and the longer they go untreated, the more amplified and permanent are the impacts on their mental and physical health. The risk of the long-term effects of traumatic experiences in even higher in younger children as they do not have the complete emotional mechanisms and a robust enough framework to interpret the events. It should also be remembered that very often the parents of child refugees are traumatised too, so they are not as able to give a secure base for the child to feel safe.

Even before the conflict, mental health care was in short supply in the region. In Syria, 21 million people were served by only 70 psychiatrists and were only two public psychiatric hospitals. Today, the need for mental health services in the region is overwhelming and supply is at the lowest possible level as resources and attention given to mental health issues are grossly insufficient and therefore there are millions of young refugees without any opportunity to express their trauma, let alone receive any support and therapy to overcome the nightmares of war, loss and forced displacement. Matthew Saltmarsh, spokesperson for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), told Majalla that improving psychological conditions for young refugees and creating contextually sensitive mental health services is an “enormous area and a huge challenge.”

“85 percent of the world's refugees are in developing countries and, therefore, the support for mental health provision is very limited in countries like Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey. The so-called psychosocial support and support for other areas like disability, unfortunately, are often limited because the resources are going into the basics of emergency response like food, water, shelter, health. Areas like mental health have been somewhat neglected in many situations because of a lack of financing and funding of agencies like UNHCR. There is in many, many cases a lack of dedicated mental health provision,” Saltmarsh explained.

Saltmarsh added that while the UN Refugee Agency has people dedicated to trying to help refugees in overcoming the burden and pain of displacement through supporting them into employment or to keep active and occupy their time, these initiatives are still “minimal and they're often an afterthought when it comes to supporting refugees.”

People with mental illness experience the compounded disadvantages of the acute shortage of mental health specialists, stigma and in many cases, having their illness ignored and dismissed. Hansen told Majalla that the NRC faces “cultural resistance” in communities where a strong stigma surrounds mental health issues. This can often bar children and their families from seeking treatment fearing that they will be labelled. “In spite of this, our results are extremely encouraging and give us a lot of hope in what we do,” he added.

This further necessitates that the development and implementation of specialised culturally appropriate methodologies for the treatment of PTSD and other disorders should be a priority.

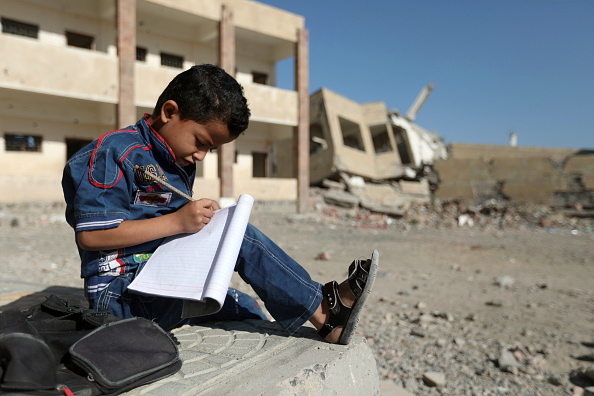

A GENERATION OF UNSCHOOLED CHILDREN

Education tends to be one of the first victims of conflict. NRC’s Hansen explained that children drop out of school because it’s unsafe to travel, because their school has been bombed, or because they have to work to support their families. Young girls also drop out of school because of early marriage, which spikes up as one of the negative coping mechanisms wherever there is widespread instability and poverty.

According to a 2015 report by UNICEF, the United Nations children’s agency, conflict in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region has driven 13 million children out of schools and some 43 percent of Syrian refugee children in Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq are out of school. The size of the crisis means that governments, whose education system were already under strain before the refugees arrived, are struggling. In Lebanon, most refugee children are living outside the formal camp system and attending local schools, where teachers are trying to incorporate them into ordinary classes. This means that classes are overpacked, each pupil receives less attention, teachers are under pressure to teach bigger classes with mixed language skills, and have to support children who are traumatised.

UNHCR's Saltmarsh explained that for children who have been out of school for years, the possibility of finding gainful employment as an adult becomes increasingly challenging. “The number of refugee adolescents enrolled in secondary school is about 23 percent. In lower-income countries, that number declines to 9 percent, while the global equivalent for non-refugees is 84 percent. When you miss out on a big chunk of secondary or further education it becomes extremely difficult just to have the skills that are needed to find jobs and to become more productive,” he said.

The NRC is concerned about the hostile environment where uprooted youth feel trapped and disaffected with few opportunities to develop their potential. “Our work is just a drop in the ocean and requires government policies to make sure young people are given the opportunities to thrive in whatever they aspire to do. This will benefit everyone – from the host countries to their country of origin if and when they return,” Hansen said.

Education gives children the skills they need to grow up to be productive and independent members of society and therefore unschooled children have negative short-term and long-term consequences, not just for the individuals, but for both sending and receiving countries. In Syria, the departure of millions of refugees, combined with inadequate schooling will cause long-term deterioration of the county’s most valuable asset, its human capital. Saltmarsh says that in the future when Syria needs it most, there will be a collective shortage of vital skills. “There's a lot of people who have not been working and who have not been in full-time education. So, firstly, you have to hope for peace and that people will return, but when they do they will need to be a lot of support from the international community to help people to physically rebuild structures and then to try to make sure that there are enough good people and staff to run public services and to make sure that the country has the ability to get back onto its feet.”

One of the factors blocking refugee and displaced children from accessing education is the documentation crisis taking shape in the region that is leaving hundreds of thousands in legal limbo, with severe consequences for their ability to access services. “There are many refugees who are still undocumented – either because they entered the country through irregular channels, or they lost their documents as they fled, or because they lost their registration with the authorities. This puts them at further risks and makes them vulnerable and stops them from accessing essential services, education for their children or jobs,” Hansen explains.

Internally displaced children are facing the same challenges. Children are often stigmatised because they were born in areas by armed groups and are not being issued the basic documentation they need to prove one’s identity which is fundamental to rebuilding their lives, NRC’s Hansen explains. In Iraq, where internally displaced people are scattered across different governorates, ensuring that the most vulnerable are identified and can obtain their rights is a tremendous challenge. Hansen says that 45,000 children displaced in Iraq’s camps do not have documents proving their identity which deprives them access to education and health care.

“This is depriving them of their most basic rights as Iraqi citizens – creating a neglected generation unable to travel between Iraqi cities and towns, barred from attending formal schools and obtaining educational certificates, and denied access to health care or state social welfare programs,” he explains.

“We need to make sure that education and vocational training are freely available for displaced youth, wherever they are and whatever their status is. Whether a young person has an ID or not or the right paperwork should make no difference to their right to education, training and pursuit of their ambitions. Whether formal or informal education, this is the basis for any improvement in their situation,” he added.

The NRC says that drastic interventions need to be designed to ensure that new generations are not lost to hopelessness and have the necessary skills and education to move forward in life. “We need to see more wide-ranging reforms that would benefit the impoverished youth who may be citizens of a host country but have been marginalised along the years for reasons of class, sectarian, ethnic and political divisions, not to mention other issues such as corruption and outdated curricula that disenfranchise a lot of youth. The only way to tap into today’s generation of young people is to aspire for equality of opportunities for all citizens and refugees,” Hansen said.

The UN Refugee Agency has for a long time advocated that education needs to be mainstreamed and invested in immediately in humanitarian disaster response rather than being an afterthought. They’ve also called for more money to go into education programs "whether that's specific programs around scholarships for refugees or creating what is known as ‘legal pathways’ for refugees to be able to move to different countries for limited periods and potentially work or study in those countries before they can go back to their home countries,” said Saltmarsh.

A FUTURE IN THE BALANCE

It is difficult to overstate the extent of the destruction which the wars in the Arab region have left behind. In Iraq, the liberation of territories from ISIS came at a great human and infrastructural cost. In Syria, the reconquest of terrorisers by Basher al-Assad came after a war which generated half the words refugees and sowed devastation across much of the country. In Yemen, the infrastructure and economy of the country have endured near complete destruction, leaving much of the population at risk of starvation and disease. While sadly none of these wars have fully ended, attention is increasingly focused on the overwhelming impending challenges of reconstruction. But these mass atrocities have left behind a traumatised, unschooled deeply divided generation, the scale and magnitude of which societies are still struggling to come to term with. The catastrophic damage done to the social fabric of the countries affected will take decades to undo. We are living in an unprecedented time in history and therefore global and shared solutions are needed. Only acting today to ensure that a generation is healing and learning and not lost will we provide a foundation for reconstruction and unlock the hope that all children deserve.

In December last year, the UN approved the Global Compact for Refugees which sets out four main objectives: ease the pressures on host countries, enhance refugee self-reliance, expand access to third-country solutions and support conditions in countries of origin for a safe and dignified return. International organizations, government officials, NGOs, activists, and scholars were all involved in developing the documents. UNHCR’s Saltmarsh said told Majalla that although the agreements have no binding value, they have created a new momentum in the world by shedding light on these issues.

“Although the Global Compact on Refugees is not legally binding, it is probably the most significant international commitment on refugee protection since the 1950s. As such, there is optimism that it can over the medium and longer term help to create new structures which can better support refugees in displacement and give them much more of a route towards independence, dignity and self-reliance.”

Although it is largely a symbolic step, advocates for refugee rights and welfare say they hope the agreement is a starting point for better international cooperation. Whether the compact will make a difference is too early to tell but it ultimately depends on the political will of states to implement their commitments and create systems to ensure meaningful follow-up, review and accountability will be crucial.

NRC’s Hasnen says that both host governments and donor governments must live up to their existing commitments and called on politicians and civil society to diffuse the inflammatory rhetoric that demonises refugees. “Anti refugee rhetoric and xenophobia is becoming more mainstream, and these vulnerable people are easy scapegoats. The end result is more misery and an erosion of hard-fought human rights. We call on politicians and civil society to buck this trend," he said.