Dame Vera is – incredibly – still alive. It was she who sang ‘There’ll be bluebirds over/The white cliffs of Dover’ when the country was battling for survival against the full fury of Nazi Germany. Bombers, rather than bluebirds, flew over Kent. Leadsom lost the leadership race after ill-advisedly assuring the press that she would make a great prime minister because she was a mother, one of the few qualifications that Theresa May lacked. Leadsom seemed not to notice that a great many other women had children, none of whom were expecting to move into Number Ten.

This Brexit saga has lasted so long now, one could be forgiven for thinking that Andrea Leadsom (along with all the other characters it has turned into household names) has been around as long as Dame Vera. The white cliffs have had a pretty strong showing too, invariably depicted by cartoonists as the ‘cliff edge’ in question when the politicians and the pundits have threatened us with a ‘no deal Brexit’. The prospect of crashing out of the European Union has led to a kind of race memory of wartime hardship and the necessity of growing one’s own vegetables. People have even invoked the old slogan ‘Dig for Victory.’ The leader of the opposition, Jeremy Corbyn, is said to be secretly in favour of Brexit, but then as the proud owner of an allotment he has a head start on the rest of us.

None of this sounds very hedonistic. In fact, the whole Brexit issue, overshadowing as it does the pressing need to solve some of the country’s long-standing social problems, has proved so time-consuming that the Conservatives have been able to continue austerity, even as they have claimed to be ending it. Libraries continue to close, schools continue to struggle to buy resources, food banks continue to proliferate along with homeless numbers in our cities, and yet Brexit reigns supreme, sucking up all the parliamentary business that Andrea Leadsom, the tuneless impersonator, announces. Even now, in the hiatus that has followed the dodging of the deadline in March, nothing else gets done.

Part of the problem is that no one has ever known how to interpret the result, let alone how to honour it. Was it a spasm of xenophobia? Was it a more chronic reaction against immigration? Was it a desire for greater sovereignty? Was it, as many believe, a revolt of the discontented and ‘left behind’ members of the British public against their politicians and the system in general?

We will never really know, for the simple reason that the referendum was a closed question, a binary choice without reference of any kind to further detail. It wasn’t even as subtle a question as the one that tormented The Clash: ‘Should I stay or should I go now? / If I go there will be trouble, /And if I stay it will be double.’

Thus, after frantic dithering, the British people decided by a narrow margin that a certain amount of trouble (go) was preferable to double the trouble (stay), but even this they decided half-heartedly, and without specifying what ‘go’ meant. Since then, we have seen a huge display of ridicule aimed at the politicians, the vast majority of whom did not want to go and didn’t see the trouble doubling if we stayed. But the politicians have surely been poorly treated this time round, as it is the British people who have lumbered them with the nigh on impossible task of reading the runes of the referendum and solving what Danny Dyer, the TV soap star, so wisely referred to as a ‘riddle’.

The ultimate revenge of the voter; that is where one can see the carnivalesque element in Brexit. Carnival has always been associated with Catholicism and with some very un-British behaviour, so when the British resort to its methods, it may not look like the ‘thighs and feathers’ shenanigans in Rio de Janeiro. There may not be much music, not a lot of jollity, and not a spectacular float in sight, except perhaps this one:

But it is carnival nonetheless because, in the way of the old medieval carnivals, it involves the befuddling of the political classes, paralysing the normal operations of government and challenging the elites. The world’s been turned upside down. The people have spoken. If the politicians are having problems making out what the people have said, well, ain’t that just the problem with politicians?

In one of my old theory books, the Russian philosopher Bakhtin’s epic work on Rabelais and the medieval world, I first learnt about the tradition of the carnival in Catholic Europe, and even as a dreamy young student I could see it was the kind of thing to give the Protestant work ethic a good name. Carnival was a time of sanctioned chaos, of anarchy really, a period in the year when anything could happen. Instead of the usual authorities, the people paid obeisance to a certifiable numskull, sometimes known as the Lord of Misrule, at whom everyone could have a good laugh. In fact, Bakhtin wrote a whole chapter on the history of laughter, advancing the notion of its therapeutic and liberating force, and arguing that ‘laughing truth... degrades power’. In his book on Dostoyevsky he added,

Carnival is past millennia’s way of sensing the world as one great communal performance. This sense of the world, liberating one from fear, bringing the world maximally close to a person and bringing one person maximally close to another, with its joy at change and its joyful relativity, is opposed to that one-sided and gloomy official seriousness which is dogmatic and hostile to evolution and change, which seeks to absolutise a given condition of existence or a given social order. From precisely that sort of seriousness did the carnival sense of the world liberate man.

This reminds one of the recent scolding that school children received from Theresa May for bunking off school to protest against climate change. The cheeky laughter of the pupil turned demonstrator undermines the pomposity of the nanny state as embodied in its starchy head teacher. It is no accident that Private Eye portrays May as a head mistress. For Bakhtin, ‘carnivalesque laughter’ is always punching upwards, directed towards something higher – towards the existing world order. Hence,

All the images of carnival are dualistic; they unite within themselves both poles of change and crisis: birth and death (the image of pregnant death), blessing and curse (benedictory carnival curses which call simultaneously for death and rebirth), praise and abuse, youth and old age, top and bottom, face and backside, stupidity and wisdom.

The ‘face and the backside.’ It was Montaigne who wrote: ‘On the highest throne in the world, we still sit only on our own bottom.’ Bakhtin’s Wikipedia entry goes on to explain, in addition to qualities of inversion, ambivalence, and excess, carnival’s themes typically include a fascination with the body, particularly its little-glorified or 'lower strata' parts, and dichotomies between ‘high’ or ‘low’. The high and low binary is particularly relevant in communication as certain verbiage is considered high, while slang is considered low.

As we shall see, the Liberal Democrats are running a campaign that seeks to utilise this aspect of Carnival and to wrest control of the agenda from the ‘bad boys’ of Brexit. By adopting the phrase ‘Bollocks to Brexit!’ they are staking a claim to slang and to the language of the lower stratum of the human body. For too long the energy of the (Brexit) Carnival has been directed at the wrong authorities, those in Brussels, while the actual authorities that rule our everyday existence here in England have escaped unscathed and even been able to benefit from subversive laughter. This is how we end up with the likes of Boris Johnson who, in the manner of a French performer of the last century known as Pétomane, has mastered the art of speaking through his backside.

At first sight, Brexit undoubtedly has a carnivalesque quality and its defiance of authority might even seem refreshing, until you realise that it is the upper classes who’ve been running the show all along.

NO CARNIVAL, PLEASE, WE’RE BRITISH

The revellers of medieval society were not so inclined to make that mistake. They knew better than we do who their natural enemies were. One only has to consider the number of revolts that took place in medieval England, by peasants for the most part, and how close they came in some cases to toppling the world order of the day. ‘When Adam delved and Eve span / Who then was the gentleman?’ Oddly enough, it helped to have a religious view of existence, insofar as it put the gentry, aristocracy and even monarchs in their place on the wheel of fortune, and so long as the wheel turned – or whenever another plague happened along – they could fall.

So, Carnival in its old, lower stratum rudeness and scatological irreverence, was a kind of prototype for insurrection. It temporarily suspended the normal rules of life and could last for as long as three months. It still does, in Guadeloupe.

Now, as we all know, a week is a long time in politics. Three months, therefore, is much longer than a long time. And if that’s the case, just how unimaginably long is three years? Because that’s how long this present carnival has been going on now, in merry England, and it is the English who are chiefly to blame for this less than merry season, though the Welsh also had a hand in it. Almost three years ripped from the pages of a nation’s history when nothing got done, when the politicians were increasingly ludicrous in their behaviour, when one carnival buffoon succeeded another and the world stifled its giggles to see this once great country reduced to an ungovernable mess. Three years of tortuous, fractious, jargon-laden inconsequence and the endless dancing of angels on the head of a pin. Three years of repeating the word ‘Brexit’, which is some kind of fossilised form of a joke that was never funny in the first place and was probably, irony of ironies, invented by a Brussels bureaucrat.

It is almost three years since the country voted in a referendum and elevated an idiot to power. But I don’t wish to malign Theresa May here. She might not inspire any great affection, but she is not an idiot. No, it has elevated the ‘will of the people’ to that high office and, like a football result, given an illusion of victory to those who ‘won’. Brexit must indeed mean Brexit. Make mine a red, white and blue one. Many of those who voted for Brexit were amazed that it didn’t simply happen, the next day if possible, as that was indubitably the will of the people.

But, unlike the transient pleasures of the old-fashioned carnival, gratification has not proved quite so instantaneous. Thus, having vanquished her child-bearing rival, May has become the long-suffering handmaiden to the decision of the electorate, more formally known as ‘Will of the People’, the highest seat of authority in the land. Will of the People is now the one who will decide every last detail of our daily lives: how much we can earn, how hard we must work if we are still productive, how many mouths we can feed if we are still re-productive, and how much we can eat if we are no longer productive. For a country with chronically low productivity, no one is safe.

So, just who is this Will of the People? His fans, by which I mean the politicians on the winning side in the referendum, will tell you he’s the creation of the biggest democratic exercise in the country’s history and that he is incredibly popular, though in the same way as marmite is popular, since almost half of the country hate him.

For three long years he has been served by his handmaiden who claims to be the only person truly to understand him and his whims. May is the people’s most unlikely servant, the daughter of a vicar and wife of a stockbroker whose ‘relatability’ is so low that she has been christened the ‘Maybot’ by satirists. When she tried to blame parliament for its failure to support Will of the People recently, she was roundly condemned for putting its members in danger. Then, soon afterwards, when she tried to speak to the people directly from her sofa in Chequers, she was so strained in her relaxed manner she made Gordon Brown’s efforts at a smile seem winsome, which until that point had only made a nation wince.

Will of the People is supreme. His handmaiden, in comparison, is a diminished figure, worn down by defeats in the Commons and before that by a disastrous election she only called to improve her majority (she lost what slender majority she had). There are times when her voice has failed, when a cough has afflicted her, when she has attempted to dance, and with every fresh failure she has diminished further. The former Chancellor, George Osborne, said after the ill-starred election that Theresa May was a dead woman walking. One cartoonist has taken to depicting her as a ghost. And yet, like the Sibyl of Cumae, it is as if she cannot die. Having asked for immortality but forgotten to ask for eternal youth, she sits in Number Ten like a caged grasshopper, shrinking ever smaller and squeaking “I want to die!” so quietly that no one, not even the rivals for her job, can hear her.

So much for Theresa May. As I said, a handmaiden.

WILL OF THE PEOPLE

It was perhaps inevitable that, given the essential inscrutability of the result, the will of the people would have to find its embodiment in a person. Cometh the hour and all that. A man who could make, in his own eloquent words, a ‘titanic success’ of Brexit. A man with charm, wit, a bizarre way with the English language and a cavalier approach to the truth. A man intelligent enough to have authored a documentary account of Europe’s indebtedness to Islam, yet populist enough to portray women in burkas as letter boxes and bank robbers. A man who, writing in The Spectator, had referred to pickaninnies with water melon smiles. A man with a Latinate vocabulary picked up in a posh school, who could nonetheless blurt out “F*ck business!” when told that business didn’t want Brexit. A man with Turkish blood who could benefit from the notion that Turkey was about to join the European Union and that Albion would be flooded with freely moving Turks. A man who had, as Mayor of London, plans to build an airport on an island in the Thames and a garden bridge across it. A man, in short, who no one could decide if he was a cunning dissembler or a complete buffoon.

Only one man had the necessary talent and charisma, coupled with apparent stupidity, to embody the will of the people and that was Boris Johnson. Who else could have kept the world of British journalism on tenterhooks and holding its breath for the answer to what way he would jump when the referendum was first called? The press camped outside his London flat to hear what he had decided. Johnson, uncharacteristically, spent the weekend in retreat from the press, mulling over his decision: would his ascent to the post of prime minister best be served by supporting his old Etonian buddy David Cameron’s campaign to remain in the European Union, or was this the time to toss friendship and loyalty aside and throw his considerable weight behind the campaign to leave.

It was a tough one. Boris underwent an entire weekend of obscurity without anyone being privy to his thoughts and with no opportunity, under the self-denying ordinance, to speak his mind, entangled in thought, racked, one might conjecture, petrified in the attitude of Rodin’s thinker, assailed by an almost clerical level of doubt. It already looked as if this dilemma would seriously erode his customary good humour. It was, quite frankly, a lamentable waste of a perfectly good weekend.

So, the man of the moment set about drafting two letters, one in which he would loyally declare his allegiance to his old mate and to his country’s future membership of the European club, the other in which he would say the precise opposite.

Finally, after completing the two drafts, he did what he always did in such circumstances – he determined which option best served his ambition and took a gamble: he would indeed embody the will of the people, but only insofar as it was the losing portion of the people. Boris saw no likelihood of being on the winning side. From the noble state of defeat, he would go on to champion the losers. It would put sufficient distance between himself and the old buddy and, you watch, his time would come. The result would narrowly go the way of remain and then he could lead the lost cause he had always cherished qua lost cause, not because he cared one way or the other since, after all, what was the point of an expensive education if one didn’t come out of it insouciant? Caring is a deeply plebeian habit of mind.

Ever the insurgent, Boris would continue an adult lifetime of sniping at the institutions in Brussels, lying about the absurdities of the bureaucrats, and biding his time.

CHAP CALLED CUMBERBATCH

Which brings me, inevitably, to Benedict Cumberbatch. One struggles, nowadays, to understand anything without the help of Benedict Cumberbatch.

When starring in ‘Hamlet’ (a play with little to say on the topic of refugees, though at a stretch one might mistake Rosencrantz and Guildenstern for spectacularly failed asylum seekers), Cumberbatch highlighted the issue of refugees after every performance in an extemporised speech, and such was his stardom that only the occasional cantankerous critic objected to these homilies. Pah, critics!

More usually, however, Cumberbatch prefers to portray the leading figures of any given period. This is the actor who persuaded audiences that slave owners were unpleasant people. It’s also the actor who gave us a penetrating insight into the enigma of a white-haired Australian geek. Sadly, however, we never saw him embody ‘the will of the people’. He might have managed the hair, which is not unlike that of Julian Assange, and the stoop would have been a doddle, but no amount of method acting would have been sufficient to pull off the distinctive body line. Hamlet, Assange and Sherlock Holmes are alike in being skinny. They also have a certain cerebral froideur in common. So it was that we never got Cumberbatch’s Boris Johnson.

Instead, we got his Dominic Cummings. Uncanny, really: the Machiavellian campaign director of Vote Leave, in a play for television by James Graham called ‘An Uncivil War’. The playwright has confessed to liking ‘disrupters’, though of course this is a professional predilection, as disrupters make good drama. I don’t suppose he likes them much in reality.

The Western world is presently experiencing an epidemic of disrupters and has to cling onto its democratic institutions in the same way sheepish footballers cling onto their family jewels when the opposition are awarded a free kick. There is a disrupter in the White House (who is very fond of another disrupter in the Kremlin), numerous disrupters in Italy (including Matteo Salvini, Minister of the Interior, and an ex-pope who retired rather than die in harness and now lingers on, like a fart in a lift, disrupting Pope Francis), a disrupter in Budapest who advocates illiberalism, disrupters on the Champs-Élysées who show up every weekend dressed in yellow, German disrupters who argue that the Second World War was mere ‘bird poo’ in the bigger historical picture of German greatness, and, of course, Steve Bannon.

Here, we have a chap called Yaxley-Lennon who didn’t like having a dead left-wing pop star’s name, so he chose the moniker of a pop star who was ‘glad to be gay’ instead. We all make mistakes. Steve Bannon reckons he’s ‘the backbone of England’, though he actually bears no resemblance to the Pennines, apart from a certain dankness. He doesn’t have a lot of disruptive vitality, to be fair, and he can’t sing for toffee. His only talent is for a bit of straight forward persecuting, mostly of religious minorities.

But Yaxley-Lennon is not the only British disrupter. These days the country has so many, it has to export them. The bulk of our disrupters are exported directly to the European parliament, but if and when we ever leave, finally, they will come back here, and from that day forward we will never get shot of them.

Dominic Cummings was a comparatively little-known disrupter until Benedict Cumberbatch decided to immortalise him. In fact, the cantankerous critics had a go at the actor for doing just that, as they thought, probably wrongly, that having the greatest thespian of his generation portraying him like this would only encourage Cummings. Sadly, the man needs no encouragement. He has already determined to his complete satisfaction that he is a towering genius. He is skinny and cerebral for a start. And did he not come up with the slogan Take back control, the most successful since I’m Backing Britain or Go to work on an egg? According to the script, he picked this up from a manual for new parents, which is possibly the only touching moment in the play.

Cummings is shown as a ruthless strategist, utterly convinced that the British people are crying out for Brexit, although he alone can hear their cries. He hides in broom cupboards, hunched over a hot laptop, calculating his next move. He draws diagrams in a frenzy, hatches plots, stares down his doubters and leads the country towards the sunny uplands with utter, ruthless determination. Throughout, he hears the faint rumble of the nation’s discontent. At one point he goes into the street and, in broad daylight, sinks to his knees, sinks his head down to the tarmac and hears the sound of the country, rumbling. Ear to the ground, see?

Only when the results come in does that rumble cease. Cummings is no lunatic. He is a visionary in the mould of Savonarola, a fanatic, a Brexit obsessive. He has a brief moment of doubt when an MP is brutally murdered and the campaigning is put on hold, but doubt seldom troubles the true Brexiteer. If those licentious paintings have to be burnt, so be it. If the Irish peace process needs to be halted and even reversed, if the entire population needs to be divided against itself, if the economy needs to be trashed, or if the rule of law needs to be challenged and our venerable democratic institutions disrupted, well, that’s what disrupters do: they disrupt.

“You lost. Suck it up! You’re all re-moaners. Get over it.”

A TALE OF TWO MARCHES

But some people just don’t know when they’re beaten. On the 23 March, the BBC reported a massive march of ‘hundreds of thousands’, which made it sound rather less massive than it actually was. In fact, the numbers easily topped one million. Even the police agreed it was bigger than just ‘hundreds of thousands’, but then they would: these days they’ll say anything to inspire sympathy.

The people who gave us Brexit were quick to condemn the marchers. Kate Hooey, a Brexit voting MP whose constituents voted to remain, reluctantly acknowledged the sheer size of the demonstration. She said the march from Sunderland, a bedraggled ‘leave’ affair organised by Nigel Farage, had never been intended to be big. It was ‘symbolic’ she said.

Other Brexiteers were more openly disgruntled. A young woman on Sky's Press Review claimed to be ‘appalled’ by it. Michael Gove's wife, Sarah Vine, tweeted that there were no leave protesters around on the day, as they would certainly have been lynched. This was a comical observation to anyone at the demonstration. Many of the protesters were young parents. There were prams everywhere, numerous pet dogs. It would have been the first time in history that a gang of toddlers, possessed by blood lust, had grabbed their hapless political opponents and strung them from the lampposts.

Demonstrations have a mood and attitude all of their own, and this one's energy was not remotely violent. There were no police to be seen. The choppers that whirred clunkily overhead belonged to the TV news channels. The whole thing had what journalists like to call ‘a carnival atmosphere’. That makes it sound noisy, though, and a bit brash. In fact, it was quietly satirical and a little bit rude. There were numerous unicorns held aloft and the phrase ‘Bollocks to Brexit!’ (possibly inspired by the Sex Pistols’ great album) was everywhere: on stickers, on badges, shouted with subversive glee. A girl who could have been no more than five or six was perched above the shuffling mass of people inching its way down Piccadilly, shouting (and she really had a voice on her) the sunnily (but not as in the newspaper) alliterative phrase. To this, the entire crowd responded with the same words as they crept past. Nowadays it has been adopted by the Liberal Democrats, leading to prim opinion pieces lamenting the lowering of the tone of public debate.

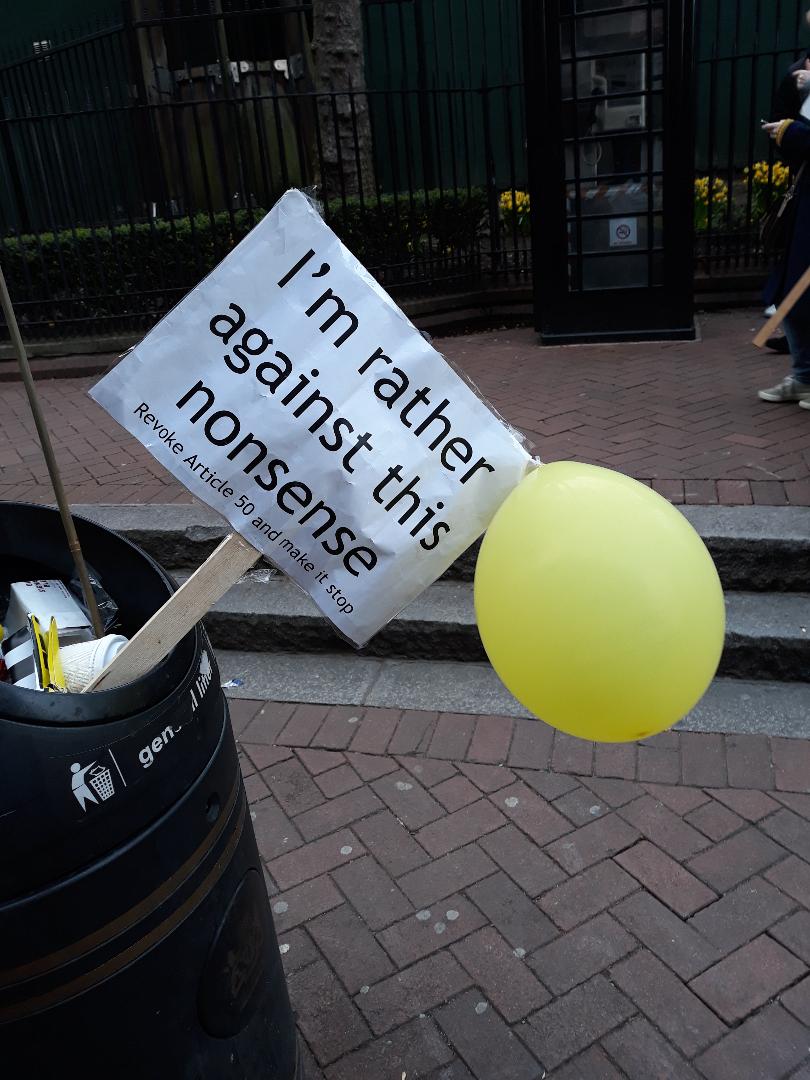

It wasn’t all colourful language. As I came back up Villiers Street later, I found a placard dumped in a bin that read: I’m rather against this nonsense. That typified the studied understatement of many of the placards.

However, outside a Covent Garden pub a man in a wheelchair sporting unfeasibly large bollocks made of soft material agreed to let me photograph them as long as I didn't take a picture of his face. And so, with the encouragement of his girlfriend, I found myself pointing my mobile at a stranger's crotch.

This was the kind of demonstration which partakes of the true carnival spirit, with the atmosphere, yes, but also the traditional subversion of authority.

The demonstration that followed, on the missed date of the country’s departure, had a more sombre aspect. Not a toddler or funny placard in sight. This was the Real Brexit Carnival. A host of disgruntled leavers, many of them classed as ‘gammons’ by their opponents, otherwise identifiable as white middle-aged men, were united in their utter disbelief that they were still in the European Union and marched on parliament to vent their anger. The Disrupter in Chief, Nigel Farage, told them to put the fear of God in their elected representatives, while the man with the name of a gay pop star – we all make mistakes – was there too, bathing in the crowd’s adulation, his face projected on a big screen opposite a dejected statue of Churchill, as he had a go at religious minorities for no apparent reason. A lot of union flags were in evidence. Jon Snow, the reporter from Channel Four News, commented that he’d “never seen so many white people in one place”.

It didn’t go down well, that comment. Well, not with the disrupters.

COMETH THE BREXIT

What do they teach them at Eton? Not how to comb their hair, tuck their shirt in or stand up straight, obviously. Foreign affairs and diplomacy are not in your average Etonian’s skill set either.

But gaming the system in whatever way the times require, check. Cultivating a flair for mendacity, check. Getting a ‘fag’ to do all your dirty work, check. None of this gets a mention in the school’s boating song.

Anyone lacking the proper mendacity and facility with lying gets his head rammed down the pan of a toilet and the cistern flushed, pronto. He is then required to learn by heart Cicero’s Second Oration against Catiline and caned on the bare nates for any grammatical errors or failures of memory, and if the errors are repeated and in sufficient number, he is nailed to the exterior wall. I’m lying, obviously. I may not have gone to Eton, but I can lie with the best of them, on paper.

Adulthood is the eventual reward for the miseries of a privileged education. Deprived of childhood, they finally get to be children from the moment they leave school. And when an Etonian comes of age, fully equipped with the capacity to deceive the populace, he is already groomed for power.

I suppose it seemed obvious to most of his teachers that Will of the People would go far, being such a good liar. And he is, of course, an inveterate one. Only the other day, when there were local elections across the country, he claimed to have voted at his local polling station and urged others to do so, despite the fact that he lives in London and the metropolis had no elections on that day. He later deleted the tweet.

While in Brussels, Will of the People would send accounts of preposterous and mostly invented bureaucratic edicts for the disgusted relish of Eurosceptic readers. He showed no regard for veracity:

Johnson did not invent Euroscepticism but he took it to new levels. A brilliant caricaturist, he made his name by mocking, lampooning and ridiculing the EU. He wrote stories headlined “Brussels recruits sniffers to ensure that Euro-manure smells the same”, “Threat to British pink sausages” and “Snails are fish, says EU”. He wrote about plans to standardise condom sizes and ban prawn cocktail flavour crisps (Martin Fletcher, New Statesman, 1 July 2016).

Boris still writes for the Daily Telegraph and was recently caught lying about statistics, by an actual statistician called Mitchell Stirling. Johnson had maintained that departure without a deal was ‘by some margin preferred by the British public.’ When it turned out this was a distortion of the truth, the newspaper, ever loyal to its mendacious star columnist, protested that the article was clearly an opinion piece, and readers would understand that the statement was not invoking specific polling – no specific dates or polls were referenced. It [the paper] said that the writer was entitled to make sweeping generalisations based on his opinions and that the complainant had misconstrued the purpose of the article; it was clearly comically polemical, and could not be reasonably read as a serious, empirical, in-depth analysis of hard factual matters.

It was all to no avail. The Independent Press Standards Organisation’s Complaints Committee ruled that there had been a ‘failure to take care over the accuracy of the article’. But hang on, failure? In this society, at least since the financial crash of 2008, there have only ever been rewards for failure, so long as you belong to the right circles, which might account for the large sums Boris gets paid for ‘sweeping generalisations’ which are so ‘comically polemical.’

Simply lying, however, has not brought him to the very threshold of Number Ten. The eye-watering school fees his parents paid equipped him with the eloquence to bamboozle the populace, yet it is not rabble-rousing speeches of gravity and foreboding that he excels in. Whenever he attempts the oratory of Churchill, his hero, Will of the People has a tendency to sound self-conscious. Soaring rhetoric is not his forte, and this is a good thing, as soaring rhetoric is not fashionable. Will is shrewd, in a way never foreseen by his most devious educators. Cometh the hour, cometh the comedian. We have seen how, on the jolly old continent, the clowns keep getting into office and spouting their populism like trick buttonholes. It’s the carnival of our times. The age did not demand some latter-day Ezra Pound with complicated theories about usury. Poetry is also out. Nor does the age demand another Enoch Powell with all those rivers of blood. Classical learning, references to the Tiber, that kind of thing, just sound too grim and portentous. Only an Ironic Enoch can hope to get under the radar and evade the liberal thought police. He needs to be a man with a confident grasp of the demotic in perpetual search of a comb. In this ancient society, almost unobserved, there has been a breakdown in the usual relationship between the Anglo-Saxons and the Normans. The elite are still the inheritors of the Conquest, but it is they who speak the most fluent Anglo-Saxon. The Norman yoke is now the Anglo-Saxon joke. That’s why the Liberal Democrats have adopted the bollocks to Brexit mantra, in a vain effort to catch up with the really rude people: Britain’s elite.

But they are doomed to failure, and they won’t reap any rewards for it. Will of the People is ruder than any of them. He is the twenty-first century’s very own Pétomane, that French showman whose lower stratum entertained Edward, Prince of Wales, King Leopold of the Belgians and Sigmund Freud (naturally) with tunes like ‘O Sole Mio’. Boris is the Lord of Misrule, the Great Disrupter. In his role as Will of the People, he is the subterranean voice of the populace groaning under the yoke of Brussels. He can win more hearts and minds with his lower stratum than the Lib Dems could ever win with their mealy mouths. Like his illustrious French predecessor, he can achieve the sound effects of cannon fire and thunderstorms, blow out a candle from several yards and deliver a passable version of Land of Hope and Glory, all from his expressive fundament, whilst being paid vast sums for doing so. The elite needed a jester and every conference season he gave them one. Now, as the highest office in the land at last seems attainable, he will give the entire country a jester for prime minister. The chief architect of the great Carnival of Brexit will bumble into Downing Street and, stooping slightly with his back to the lectern, entertain an adoring public with his very own rendition of ‘Ah Sole Mio’. That’s Boris for you.