Iran has recently been revisiting a familiar threat: to block the vital Strait of Hormuz. On April 22, the United States announced it would end sanctions waivers for countries importing oil from Iran and demanded that buyers, including China and India, stop purchases by May 1 or face sanctions, with the objective of ending all Iranian oil exports as part of the President Trump’s campaign of confrontation and pressure against the Islamic Republic. In apparent response, Alireza Tangsiri, the head of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps navy force said that “if we are prevented from using [the Hormuz Strait], we will close it. In the event of any threats, we will not have the slightest hesitation to protect and defend Iran’s waterway.”

WHY DOES THE STRAIT OF HORMUZ MATTER?

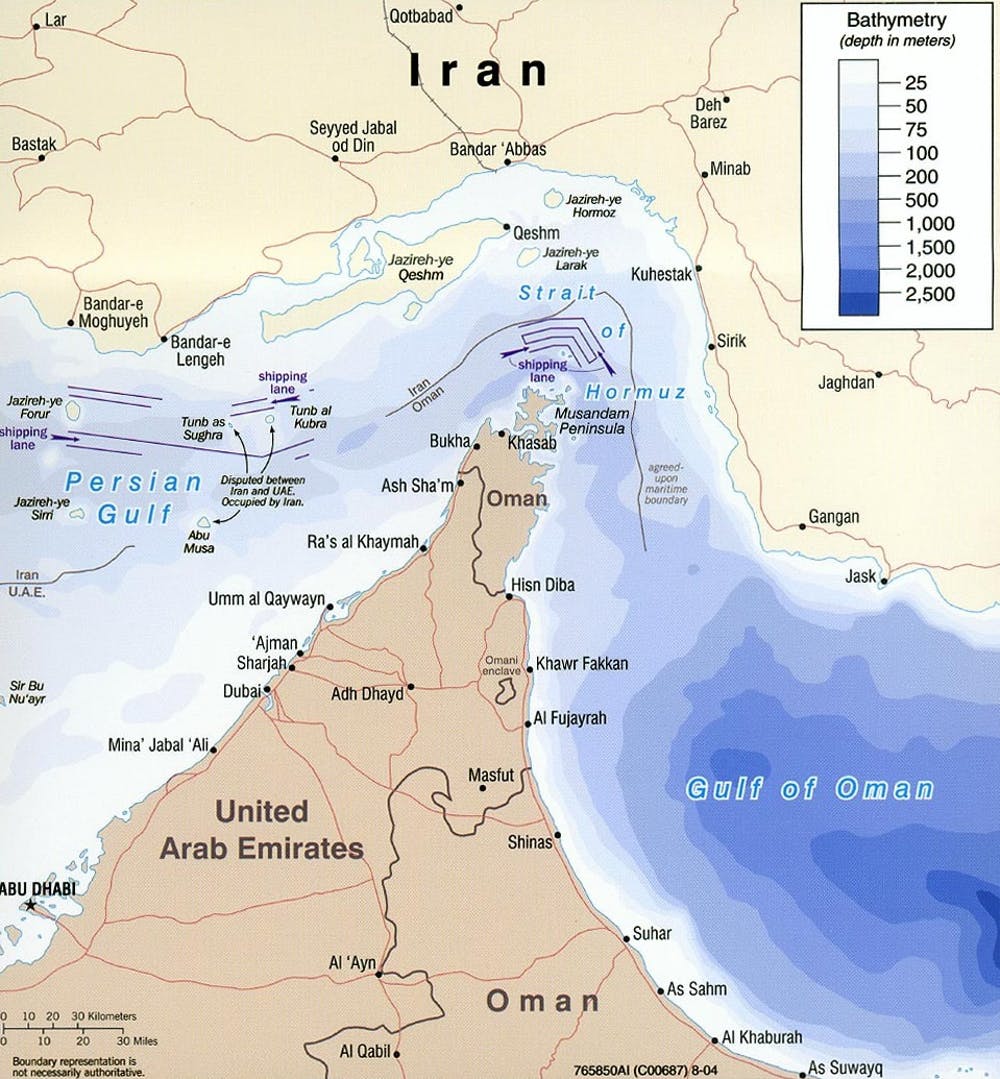

The Persian Gulf and the Strait of Hormuz are crucial not just to regional security, but also to the global economy. The vital waterway is one of the most important trade routes in the world and the most important maritime route for black gold. It lies between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman, providing the only sea passage for crude oil from many of the world’s largest oil producers - including Kuwait, Bahrain, Iran, raw and the UAE - to markets in Asia, Europe, North America and Beyond. Roughly around 40 percent of global seaborne oil exports pass through the narrow waterway, totalling about 20 million barrels of crude oil per day.

The passage has been at the heart of regional tensions for decades and while Iran has made several threats to block the waterway in the past, whether realistic or not, “these threats dramatically affect market certainty because the worlds biggest oil or natural gas importers - including the US - depend on the secure passage of shipping through the strait,” writes Firas Elias of the Washington Institute for Near Far East Policy.

The renewed threats and the prospects of reduced oil imports from Iran and instabilities in the region have prompted a surge in oil prices to six month highs and as long as the global economy remains so critically reliant on the supply of oil, even a partial or short-term closure would likely see a dramatic increase in oil prices, and spread fear and contagion through the global financial markets.

Based on international law, Iran cannot block access to the Persian Gulf through the Strait of Hormuz and suspend or close down the freedom of commerce in those waters. According to Article 37 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (“UNCLOS”), Hormuz is an “international strait” because it is the only gateway between the Persian Gulf and the open sea. The law says that the right of transit of ships in all such straits “used for international navigation between one part of the high seas or an exclusive economic zone and another part of the high seas or an exclusive economic zone” should not be suspended.

While the Iranian parliament did not approve the 1982 agreement, the Iranian government has signed it which means it is committed to avoiding any action that would violate the convention. However, at the time that Iran signed the convention, it announced that it would only recognise the “right of transit passage” for countries that had also joined the convention, and while the United States recognised provisions of the agreement as operative parts of customary international law, it is not a party to the treaty.

HOW SERIOUSLY SHOULD THESE THREATS BE TAKEN?

The current threats are reminiscent of previous statements that the Iranian leadership have been making for years when tensions with the US have increased. In 2008, citing fears of a U.S. or Israeli attack, the commander of the IRGC, Mohammad Ali Jafari, threatened to close the Strait of Hormuz in retaliation. During the 1980–88 Iran-Iraq War, both sides targeted one another’s shipping as part of a total war effort, raising fears that Iran might attempt to make the Strait of Hormuz unpassable.

In 2012, in response to sanctions by the US and EU against the country’s nuclear program, Iran’s navy chief said it would be “easy” to block the strait, while its vice president warned that not a "drop” of oil would pass through it if more sanctions were piled onto Iran. But even though the US went ahead with those sanctions, Iran did not act on its threat.

These past threats may have lessened the gravity of this most recent claim, but Iran’s newest statements in response to Trump’s sanctions are happening against a different backdrop and therefore cannot be ignored. Back in 2012, the Obama administration was negotiating the Nuclear Deal which was signed in 2015, and therefore the threats were downplayed. But the current administration has withdrawn from the agreement, formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), and reimposed heavy sanctions while pursuing a heavily focused anti-Iran policy in the region while building on its strong ties with allies such as Saudi Arabia and Israel, who view Iran as a major destabilising force in the region and their primary adversary. Another major difference between previous threats and today is the recent decision by the Trump administration to declare the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Command (IRGC) - which is already designated as a terrorist group and subject to powerful sanctions - a Foreign Terrorist Organisation (FTO). The FTO listing adds criminal liability for knowingly providing material support for the group. By definition, terrorists are non-state actors — so this designation for a foreign government’s military is a major first on the international stage and therefore the symbolism of the decision is very important, even if there are few practical advantages.

THREATS ARE EASIER SAID THAN DONE

Defence and energy analysts have fretted over the possibility that Iran could try to choke off maritime traffic in the strait for years, but threats are easy to make. In reality, it would be extremely difficult for Iran to close it completely for an extended period of time.

Iran’s ability to close the waterway to traffic is in doubt thanks in part to the presence of the U.S. Fifth Fleet, which is based in Bahrain. The U.S. naval presence has been anchored for years in Manama, Bahrain, not far from the Strait of Hormuz and would make it extremely difficult for Iran to choke off traffic.

Iran’s closure of the Strait is also unlikely to involve employing naval forces to physically occupy the waterways because its naval capabilities are ill-equipped for total closure.

Amy M. Jaffe, senior fellow for energy and the environment and director of the program on Energy Security and Climate Change at the Council on Foreign Relations says that there is the question of whether Iran could use “asymmetric warfare tactics, such as swarming speedboats and missile attacks, but the possibility of a decisive international military response led by the United States makes such an endeavour extremely risky for Iran and its military.”

Jaffe adds that Iran would likely use more clandestine approaches, such as cyber attacks on neighbouring state oil facilities. “Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have alternative pipeline routes that can bypass the Strait of Hormuz. In the case of Saudi Arabia, upward of 6.5 million barrels per day in exports could bypass the Persian Gulf,” she said.

Iran could also make a less drastic but still dangerous escalation in the Strait by utilising an Anti-Access/Area-Denial strategy (A2/AD) strategy - an attempt to deny an adversary’s freedom of movement on the battlefield. Michael Connell, head of the Iran programme with U.S. non-profit research body CNA, said of all Iran’s capabilities, mines were probably the one that caused the most concern. He also said a misjudged incident which would trigger direct fire was a more likely scenario than a blockade of the Strait.

The U.S. has said it would use minesweepers, warship escorts and potentially air strikes to protect the free flow of commerce but reopening the Strait could be a lengthy process as mines would take some time to clear, causing turmoil in energy markets that could ripple across other assets.

Anthony Cordesman, a defence analyst at the Center for Strategic and International Studies says that in the event of any Iranian effort to mine the Persian Gulf or block the Strait of Hormuz, Washington has a lot more tools in its arsenal than minesweepers — and that could be enough to dissuade Iran from ever seriously trying.

ECONOMIC SELF-HARM

Unlike previous calls to close the strait to all shipping, the latest threats seem aimed more specifically at Washington, but the U.S. economy is “less exposed now to oil price shocks than in past decades due to the lower oil intensity of the U.S. economy”, says Jaffe. “Still, high gasoline prices can derail consumer spending, especially on durable goods such as cars. At the same time, an oil price shock in the developing world could cut into countries’ appetites for U.S. goods and services,” she added.

By closing the Strait, Iran would not only be harming its neighbours and the nations that import oil from the Gulf region: It would also have a regressive impact on Iran’s interests by causing considerable economic self-harm as the nation is also highly dependent on the Right of Free Passage through the Strait. Iran’s ability to wage the so-called “oil weapon” response to US sanctions may also be jeopardised because of its weakening economy. As John Allen Gay and Geoffrey Kemp explain in War With Iran: Political, Military, and Economic Consequences: “Eighty-five percent of Iran’s imports come through the strait, and the oil exports so crucial to the Iranian government’s solvency mostly flow out of it. Iran would be cutting off its own lifeline if it closed the strait, and it would have to live on its already dwindling currency reserves. Iran would also be inviting attacks on its own oil facilities by vengeful neighbours, and it would isolate itself internationally.”