A FRENCH ARTIST IN THE INFERNO?

In the days of Queen Victoria, a traveller by the name of Gustave Doré came to witness the greatest city on the face of the earth. Twice the size of Paris, it was easily the largest concentration of humanity the world had ever seen. Though the Frenchman called his trip a ‘pilgrimage’, he seems to have been slightly intimidated by the shrine – he was accused of inaccuracies, owing to a reluctance to sketch in public. Nonetheless, the scenes he etched have an accuracy of a different kind, a fidelity to the descriptions by William Blake and Charles Dickens of a vast conglomeration of wealth and deprivation. Doré shows scenes of people crowding the chaotic, furiously productive metropolis, travelling in various modes of transport, labouring in the fish market and slowly dying in cramped slums.

Since that time, London has changed, but it still has the capacity to intimidate. Come back after a month away and it never looks quite the same. The town, sometimes referred to as ‘the Smoke’, is still dirty, still constantly growing bigger, upwards if not outwards, and it can still have the unreal quality T.S. Eliot saw in it:

Unreal City

Under the brown fog of a winter dawn,

A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

I had not thought death had undone so many.

Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled,

And each man fixed his eyes before his feet.

The fact that this vision was inspired by Dante’s Inferno also chimes with the French artist’s preoccupations. Along with scenes of London, Doré is famous for his illustrations of the old Italian poet’s visit to Hell.

I knew Doré’s pictures as a boy, and on the few occasions my father brought us from our home in Essex, the train journey reminded me of one picture in particular. It showed a sweeping curve of terraced houses, their little backyards hemmed round with walls and the people’s washing hung out in sagging lines between them. I remember thinking that the effort to keep their clothes clean was doomed, given all the filth in the air. If you peered closer, there were tiny people pottering in their backyards, but what really struck me were the chimneys above, whole forests of them, while over the entire scene loomed railway arches. A train clattered its way across the farthest one, spewing more muck. Vincent van Gogh would later remember that train and show it chuffing over an arch in The Yellow House (1888).

By the time of those first visits I made to London, the steam trains had long gone, and I never saw a row of terraced houses quite like Doré’s, probably because he had let his imagination get the better of him and they didn’t actually exist. I did, however, see plenty of brick houses whose yards came up to the railway lines. You could see right into their bedroom windows. I always felt sorry for the people who lived like that, their private lives exposed to the eyes of thousands of strangers by day and their sleep disturbed by freight passing through in the night. It never occurred to me that they might have grown accustomed to the din and slept as soundly as I did.

A DUTCH ARTIST IN PURGATORY?

The new exhibition at Tate Britain describes how Van Gogh, a painter famed for his pictures of the radiant light of the south of France, dwelt amid the noise and the brown fog of London for a while. He spent almost three years of his formative twenties in the belly of the beast, from 1873-5. It seems on the face of it an environment he would have hated, and he did have low moods there, but one can also find enthusiastic reports in his fifty odd letters from the time. Years later, after seeing a painting of the banks of the Thames near Westminster, he exclaimed “I felt how much I love London.” We learn that he greatly appreciated Constable and Millais, and that he was also an avid reader of English literature (Dickens, for instance, though sadly not Blake). He even drew little sketches of the city in his correspondence.

There is a vast amount of information like this, but from the point of view of the exhibition’s claims, there is a very simple problem with it – the fact that, at this stage in his life, Van Gogh did not consider himself a vocational artist. Soon afterwards, back in Holland, he would begin to take an interest in sketching and painting people, and one might easily see the seeds of this fascination with the poor, or with workers, in the reading matter of his London years and the prints (known as ‘black and whites’) he collected, among them Doré’s series, but the stubborn fact remains that the artistic career was ahead of him, and he might well have developed such sympathies before ever setting eyes on London.

For this reason, the single most interesting testament to his time in the Smoke comes from years later, mere months away from his premature death by suicide, when Van Gogh is confined to a mental asylum in the south of France. Unable to go out and paint in the open air as he preferred, Van Gogh worked instead on what he called a ‘translation’ of another artist’s work. It is a pivotal image in this exhibition, as it amounts to the only time Van Gogh painted an aspect of the megapolis. The particular aspect is Newgate Prison, a favourite location for Dickens, but also the subject of a Doré etching. The prison is no more, but it stood where the Old Bailey now stands and was a notorious place, known for its nastiness and the corruption of its guards. In the original black and white, we see men walking monotonously in a circle in some kind of exercise yard. Three guards stand and watch. The yard is at the bottom of a hexagon of tall brick walls and from above a feeble light gropes its way down from the heavens. The scene is utterly oppressive. The only relief afforded us, or the prisoners, is an uncharacteristically sentimental touch, almost worthy of Walt Disney: way up on the wall, clearly delineated against the grimy brick, two butterflies seem to promise some kind of redemption.

Van Gogh’s ‘translation’ is both faithful to the original and transformative. He retains the sentimental butterflies in his signature yellow, though now they are harder to make out. The men still trudge hopelessly in the same direction, but he has lit the scene far more, and with the light he has added colour. There’s a lot of rusty brown in the walls and the exercise yard is paved in blue. In combination, the shadows as the men plod and the lines of the flagstones seem to reproduce the men’s motion.

From the psychiatric hospital, Vincent had written to his brother Theo asking to be sent prison scenes like this. ‘The prison was crushing me,’ he wrote, ‘and père Peyron [his doctor] didn’t pay the slightest attention to it’. So it was that his thoughts went back, not to the pleasures and excitements of London, but to the sorrows and tedium of Newgate; so much so that (as the curator of the Tate’s exhibition, Carol Jacobi, pointed out to me) one of the men is probably a self-portrait. It is not the main figure that turns its head to look at us, but a smaller figure in the background, staring out blankly. It has a ginger beard.

Apart from the obvious specificity of this painting, there is little to suggest that Van Gogh really thought very much about a city he had visited so many years before. To point out, as the exhibition does, that a late portrait includes one of Dickens’ books on the table suggests clutching at straws. The room where we see one of his glorious pictures of sunflowers from his time in Arles is let down by the insistence on displaying inferior paintings of flowers around it, by British painters that followed him. It actually seems unfair on the lesser works to force them to sit in the presence of such obvious genius. In the last room, even a triptych by Francis Bacon, a painter who pretty much shunned the outdoors, pales next to the little sketch it was based on, of Van Gogh pootling along a Provencal country lane on his way to ‘work’. What, one is bound to ask, would Bacon, the claustrophobic painter of sexual angst and apocalyptic dread, really know about the sheer joy of colour and light?

The aim of the exhibition is a worthy one, but in the end, it is quite unable to compete – just as the imitators’ flowers are unable to compete – with the mesmerising beauty of a handful of Van Gogh’s works. Transcendently marvellous as ever, they seem to shine with life and promise like newly-hatched dragonflies. You have to tear yourself away, prise your eyes off them almost, to look at anything else. I found it quite painful to take my leave of them.

For this reason, it seems pointless to dwell on the thesis of the exhibition. Far better to talk about the handful of pictures which steal its thunder.

VAN GOGH’S BLUE PERIOD?

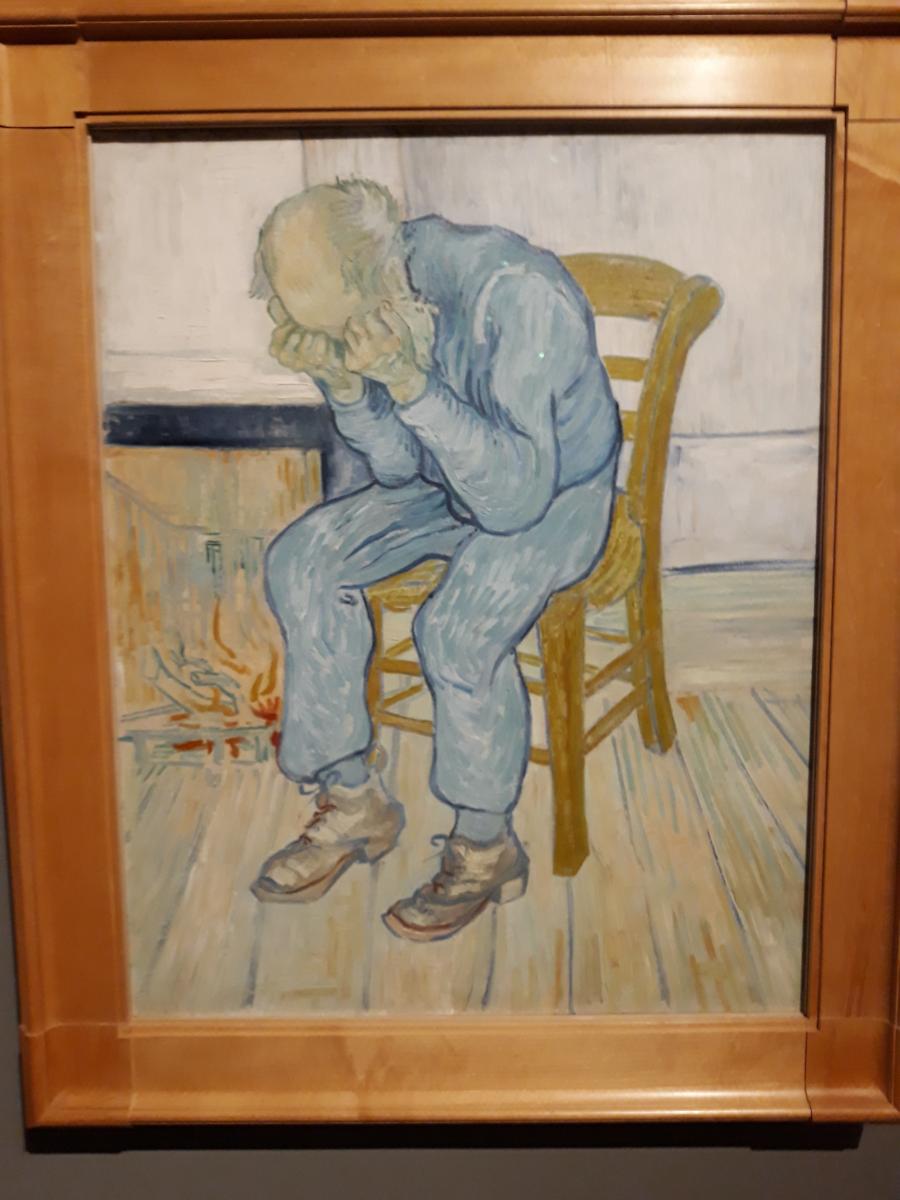

It is an anachronism, of course, to speak about Van Gogh’s ‘blue period’, a phrase exclusively associated with early Picasso. Nonetheless, another translated picture, this time from the earliest period in Vincent’s work, shares the colour and features of a Picasso. In both cases, the images are marked by sympathy for the plight of the poor and the lonely. The old man of At Eternity’s Gate started out as a drawing, but Van Gogh returned to it in paint. The subject, his head buried in his hands – a typical pose in the early works – wears blue trousers and a blue shirt and is seated on a chair we recognise from another picture, the simple chair he used to contrast himself with the more aggressive and frightening personality of Gauguin when they were both working in Arles. I shall return to chairs impregnated with the personalities of their occupants later.

Picasso shared the interest in poverty and distress while his milieu was similar to Van Gogh’s. In his early years, the Spanish painter was often penniless and lived in some very insalubrious rooms, along with his fellow bohemians. Even after he’d achieved success on an almost unimaginable scale, Picasso had a bohemian air about him and remained loyal to the Communist Party, but he completely lost touch with the subjects of his early pictures and became increasingly preoccupied with endless variations on the nude. Into that preoccupation the Guernica picture intruded as a rare spasm of the old empathy, but otherwise a fairly heartless self-indulgence accompanied Picasso’s success. The empathy that Van Gogh took with him to London (it is hard to believe he discovered it there, and it seems to have had a lot to do with his religious upbringing) never left him. The nude was a matter of no real interest, though there is a peculiar example in this exhibition, its blockish awkwardness suggesting an exercise rather than genuine curiosity. Picasso would do more to the naked female form than simply reduce it to blocks; he would treat the nude as an endlessly malleable object, taking it apart like a schoolboy attempting to reverse-engineer a broken watch in the vain hope of making it move again.

No such experiments had any place in Van Gogh’s work, but who knows, maybe his comprehensive lack of success and early death saved him from this kind of indulgence. The absence of a wider audience beyond his loyal brother and the sitters for his portraits lent his work a chaste air in comparison, a sort of privacy, like that of a diary. It would have made all the difference if he, anticipating Picasso, had been famous enough to pay for his meals by doodling caricatures on the restaurant’s napkins. Instead, the hand-to-mouth desperation of Van Gogh’s obscurity as an artist preserved his devotion to painting from any ulterior or venal motive. He could only realistically hope to please himself. For this reason, there is a sense that we are privy to the artist’s unadulterated experience. It is never mediated by fame or the requirements of a dealer, it is unaffected by trends or the taste of strangers, and it is entirely unhindered by a desire to impress. Van Gogh is painting because he feels the need to, and the pictures, like the long letters to his brother describing them, are the record of a private quest.

Perhaps this is why the famous self-portrait (destroyed in the war) that so fascinated Bacon, of Vincent ambling though the French countryside with his canvas and brushes at the ready, is so affecting. When Van Gogh went about his business, he had no anticipation of his posthumous fame. He was as innocent of his belated success as he was ingenuous in his approach to poverty, to misery, to women, and to all the commonplace realities around him. There isn’t even a hint of protest in the picture of the man despairing at his fireside, because who would possibly hear the protest? Instead, there is the simple urgency of fellow feeling. Just as surely as we occupy the here and now, Van Gogh occupied his own time. It was not the there and then for him, as he had no illusions of artistic immortality.

Van Gogh shares the same innocence as Blake’s – childlike, almost unbearably poignant – as they both found it hard to make money. They knew the same predicament of obscurity and they were both driven by what they saw, in Blake’s case with the mystic eye, in Van Gogh’s with a fleshly eye that seems to see beyond the flesh. Perhaps clear-sightedness depends on a lack of self-consciousness. Though his every action was being watched by the future, Van Gogh thought he was invisible.

This ignorance of his own fame is what the elegant art galleries or the exorbitant auction houses cherish about him. He’s like an ascetic saint. The allure and mystery of his work lies in his utter ignorance of its illustrious and over-priced posterity. In an art world where everyone has to know the price of everything and the value of nothing, Van Gogh’s art doesn’t know it will ever have a price. Like St Francis, he will be canonised too late to know about it. So, when Van Gogh sees a landscape, or a person, or even a piece of furniture, he sees it with utter honesty, with his own eyes and lives alone with its beauty. Like life itself, beyond the wage slavery of the satanic mills, his work is pure value, beyond money.

STARS, AS SEEN FROM A GUTTER

Indeed, it would be hard to imagine a less worldly artist than Van Gogh. Oscar’s Wilde’s words from Lady Windermere’s Fan – that we are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars – might as well have been framed with him in mind. This absence of materialism can give his vision cosmic reach. In an article written for the New Statesman, the novelist Margaret Drabble testifies to a longstanding admiration for Van Gogh that verges, quite candidly, on hero worship. She reflects on his attitude to the night sky, a subject he claimed was always ‘on his mind’:

He saw the stars as planets like ours, which we might reach in death. “Just as we take the train to go to Tarascon or Rouen, we take death to go to a star.” There, he fancied, the great painters of the past might work on. He wrote to Theo: “The sight of the stars always makes me dream in as simple a way as the black spots on the map, representing towns and villages, make me dream.”

That idea of death as resembling a train journey across France (Tarascon is a town near Arles) manages so instantly to combine the humdrum with the sublime.

It is also a modern version of a medieval vision, as much indebted to Doré’s illustrations of Dante’s paradise as it is to the train trundling above the heads of London’s poor. Dante was able to travel through the Ptolemaic universe, and even to see earth as a puny rock from afar, because he had shed all links with the material world. The gruesome sights of hell were forgotten in the radiant light of the spheres, where the souls of the blessed are in such a state of harmony that they form geometric shapes, constantly changing, like the murmurations of starlings at dusk. This was the kind of community of artists Van Gogh must have had in mind for the yellow house in Arles, a gathering of harmonised visionaries toiling to create beauty together. Creation has not fallen in Van Gogh. It is the abode of spirits, just like Blake’s universe. Gravity, on the other hand, comes from sin, hence Blake’s disdain for Isaac Newton, its discoverer. The opposite of sin is the everyday ease of interstellar travel. There would be no gravity to hold the community of artists down. Just as Dante had forgotten his sin after bathing in the river Lethe, so the defiance of gravity would be possible for men who had forgotten the allure of material wealth and taken to the air, maybe even living on it.

This confidence in art as a spiritual medium underpins the mysticism in Van Gogh. It may not be as declamatory as Blake’s, but it is there, nonetheless, in his raptures over colour, and this colour can even extend to the apparently cold blue of the stars, in which Van Gogh saw warm reds along with the greens, lilacs and purples. He habitually painted the stars as yellow and white splotches, like irregular fried eggs. He never saw them as twinkling tamely, or as the symbols of anything, as if on a flag, but as the exuberant bursts of distant suns.

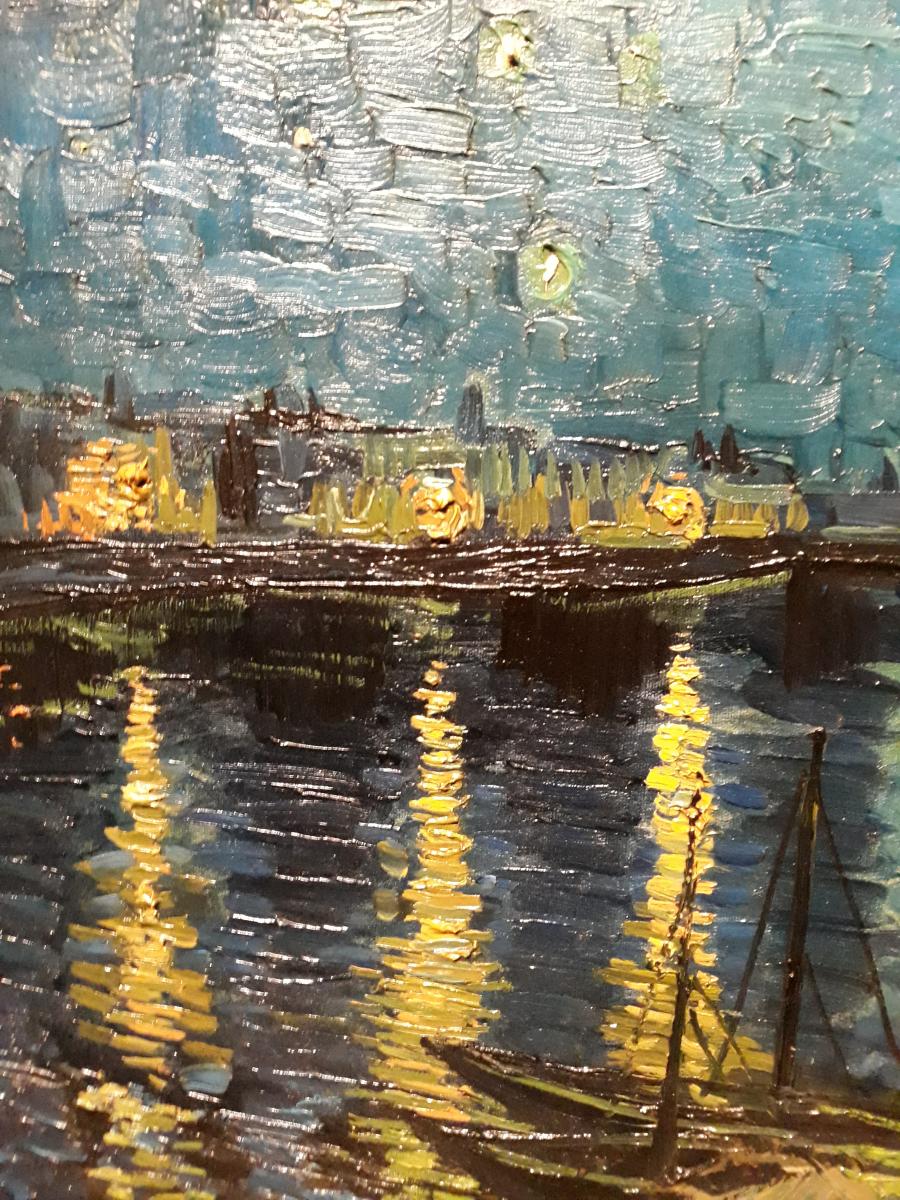

There are two starry night paintings. Perhaps the most famous is the one in which the night sky swirls in a huge breaking wave that Van Gogh, a great fan of Japanese art, remembered from Hokusai’s masterpiece. But there is also an earlier Starry Night which may well have been influenced by scenes on the Thames, in yet another picture by Doré, where the gaslights running along the embankment were reflected in shimmering verticals by the river. Van Gogh owned a print of the picture, but his own, set in Arles, transcends it as completely as his version of the Newgate prisoners.

The picture has two figures on a shoreline and the wide sweep of a bay lined with the same gaslights, with a canopy of stars overhead. What is immediately striking is the paint. The canvas is covered in a free-flowing slick of oil, the kind of impasto he employs in his wheat fields, with diagonal strokes of the brush in the foreground, horizontal strokes in the middle that show the waves breaking up the vertical of reflected gaslight, and then in the sky a confusion of smaller, vertical and horizontal patches of dark and lighter blue, interspersed with reversed fried eggs, their ‘yokes’ emanating from white centres. The paint is so thick it has angles and picks up the light of the surroundings in different ways according to how you approach the picture, as if the stars are on a background of crumpled silver foil.

When he reached Arles, he was caught up the excitement of light, even in a night scene such as this. He also painted fields, his little house, the objects inside the house. It is astonishing how little he was interested in Arles itself, with its ancient ruins (a magnificent amphitheatre, which totally failed to impress him), its civic buildings and pretty squares. None of this gets a look-in with Van Gogh; he might as well have moved to a village. Just as he was apparently unmoved by London and Paris, so the urban landscape of Arles did not fire his imagination. He did, however, paint a night scene in a street, the fried eggs of the stars above and people sitting under an awning of the purest yellow.

He also painted another night scene, this time in a dive he and Gauguin frequented, along with the city’s night hawks, and he used colour to recreate the seediness and despair of the place, raking the floor wildly so that the billiard table looks ready to lunge out of the plane of the painting. And to do all this, he stayed up for three nights and slept during the day. The result was a waking nightmare of dissolution, The Night Café, which appears in the Tate’s exhibition only as an innocuous drawing. It is the colours that carry the sense of menace. Van Gogh spoke of the finished piece, with its ‘oppressive’ combination of red and green, as one of the ugliest pictures he had done. It is worth quoting the excited description he gave of it to his brother Theo:

The room is blood red and dark yellow with a green billiard table in the middle; there are four lemon-yellow lamps with a glow of orange and green. Everywhere there is a clash and contrast of the most alien reds and greens, in the figures of little sleeping hooligans, in the empty dreary room, in violet and blue. The blood-red and the yellow-green of the billiard table, for instance, contrast with the soft tender Louis XV green of the counter, on which there is a rose nosegay. The white clothes of the landlord, watchful in a corner of that furnace, turn lemon-yellow, or pale luminous green.

The very next day he adds:

In my picture of the Night Café I have tried to express the idea that the café is a place where one can ruin oneself, go mad or commit a crime. So I have tried to express, as it were, the powers of darkness in a low public house, by soft Louis XV green and malachite, contrasting with yellow-green and harsh blue-greens, and all this in an atmosphere like a devil's furnace, of pale sulphur. And all with an appearance of Japanese gaiety.

This is an exceptionally detailed insight concerning his style. Perhaps as a result of the comparison with Gauguin, who was painting the same scene (but more conventionally), Van Gogh wants to explain what he’s attempting to convey. ‘It is colour not locally true from the point of view of the stereoscopic realist,’ he says, unusually self-conscious, ‘but colour to suggest the emotion of an ardent temperament.’ Who knows, this remark may even be a little dig at his fellow artist. Or else he has picked up a way of talking about art, something with a theoretical air about it, from Gauguin, after hours of heated discussion to which he was not accustomed.

This element of comparison brings us to the matter of the chairs. There are two, and one of them can be seen in the National Gallery in London. It is his own chair in the yellow house in Arles, and it is very yellow, but also has tinges of green, blue and russet. It’s a solidly built, simple chair with a wicker seat, the same chair as the old man in blue sits upon, and on the woven seat he has placed his pipe and tobacco. The scene is the kitchen. On the floor are brown tiles, raked as crazily as the boards in the nighthawks’ dive.

Things did not go quite as planned in his artistic community. At first when Gauguin arrived from Brittany there was great optimism. Van Gogh had painted the sunflowers to decorate his fellow artist’s room and it was promising that Gauguin knew how to cook. But Gauguin was no angel and harmony was not his speciality. He began to criticise Van Gogh’s style. There may even have been some rivalry over a woman. Certainly, Van Gogh was moved to do something very uncharacteristic, attempting to attack Gauguin with a razor and then, notoriously, attacking his own ear. We may never know the details of what went wrong between them both, but Gauguin was not the chaste, ascetic kind. He was worldly and cynical. Already a well-known figure in the art world he expected to sell. It’s possible he came to see his host as a simple soul, maybe even a bit of a bumpkin.

The best we can intuit from all this comes from the second chair Van Gogh painted, the one belonging to Gauguin. It is as close to an arrogant chair as one could imagine. In stark contrast to the simple, rugged, workaday chair in the kitchen, Gauguin’s chair is blue and red, its curves are pretentious and self-involved, it has a showiness about it that’s echoed in the flowery carpet. The colours are as oppressive as the ones in the all-night dive. On the wicker seat of this chair stand a single candle and some books. Gauguin said Van Gogh read too much, by candlelight apparently. It’s a neat bit of revenge for hurtful remarks.

In an article on these incredibly expressive pieces of furniture, the redoubtable Jonathan Jones suggests they are a reference to the empty chair in Dickens’s study. He means a picture of the writer’s study at Gad’s Hill by Sir Samuel Luke Fildes. This would imply that Van Gogh wished himself and Gauguin dead, which is subtly different to taking a train, celestial or terrestrial. A homicidal or suicidal train, perhaps.

I don’t buy this morbid interpretation. Rather, I think the mystery of the chairs is the closest we can get to a statement by Van Gogh of artistic independence. He sees the two chairs in the way only he can see them. It is an admission that artists do not belong in the same gallery, let alone in the same living quarters, and that their marriages are not made in heaven. He might not be wishing Gauguin dead as such, but he definitely wants rid of him. As we know, there was a very mundane train station close at hand.

A HORSE CHESTNUT TREE

If I’m right, Van Gogh knew very well that he was doing something different to his contemporaries. He doesn’t appear to have known Blake, but there is a strong similarity in what they were aiming for: no less than a cleansing of the doors of perception in order to glimpse infinity.

There is an argument for Van Gogh not being regarded as a painter at all, but as a kind of one-off pioneer of a way of seeing that no one has ever successfully emulated. He spiritualises whatever he sees. There is even a kind of animism going on.

Take the utterly alive horse chestnut in bloom, displayed about half way through this exhibition. It has nothing to do with the thesis of the show or with London. It also has nothing to do with Arles or with any city, and nothing to do with art history. The only thing human about is its rapt human witness.

Yet it is more alive than any horse chestnut I have ever seen, because I couldn’t see it the way he does, no one could, hence the disappointing efforts of his imitators. If artists are not as special as Van Gogh – and his like comes along two or three times a century – then they are jobbing, ephemeral doodlers, mere decorators really, not worth the time of day except for prettifying interiors. Van Gogh makes you impatient with other artists like the purveyors of adulterated goods. You long for the pure stuff, like this vibrant, more than real tree, and once you’ve set eyes on it, you can’t get enough. It’s a glimpse of infinity. No wonder it’s so difficult to tear oneself away.

The EY Exhibition: Van Gogh and Britain, curated by Carol Jacobi, is at Tate Britain in London till 11 August 2019.