The Last Englishmen: Love, War, and the End of Empire. Deborah Baker. Graywolf Press, 2018. 352pp.

The Last Englishmen: Love, War, and the End of Empire. Deborah Baker. Graywolf Press, 2018. 352pp.

The pupils of Miss Higgins’ School in Calcutta had lined up neatly for the photograph, the girls’ shoulders draped by braids, the boys’ knees peeping below shorts. Their tropical uniforms blazed brightly in the black-and-white photograph. Many of the children, including my mother and my uncle, were Bengali. Some were European, and at least one was half-Bengali, like me. “Her uncle was W. H. Auden,” my grandmother said, pointing to a girl named Anita.

If I didn’t know who the poet W. H. Auden was when I first saw these pictures from my mother’s 1950s schooldays, I knew nothing whatsoever about his brother John Bicknell Auden, Anita’s father, until reading The Last Englishmen by Deborah Baker. Auden is one of the leading characters in this group biography of young British men who set out for India in the 1920s to work as imperial administrators. They went expecting to do their bit maintaining the “jewel in the crown” of the British Empire, as generations had done before them. Instead, they found themselves witnessing the demise of the British Raj, when a long nationalist struggle culminated in 1947 with the partition of British India and the independence of India and Pakistan.

Fighting for independence from oppressive imperial rule can look in retrospect like one of those black-and-white choices—resisting fascism is another—where it seems obvious what stand anyone with principle would take. What the deeply researched, marvelously portrayed life stories recounted in The Last Englishmen show is just how muddled these world-historical changes actually look when you’re living in the middle of them. That makes the book a valuable supplement to the more conventional accounts of decolonization as a process driven by clear-eyed activists and historical logic. If anything, histories like Baker’s may be precisely what are needed in the present heated moment, as reminders of the many ways in which people find their way through political transformation.

IMPERIAL MEN

John Auden was fresh out of Cambridge when he traveled to Bengal, the most populous province in the Raj, in 1926. He was there to take a job with the Geological Survey of India. His first assignment had him surveying steamy, smoky coalfields north of Calcutta, but he dreamed of exploring the fractured peaks of the Himalayas. Auden was one of many young Europeans fired up by an intensifying competition among European powers to be the first to summit Mount Everest. Whoever climbed Everest, ran the implicit logic, was on top of the world.

Baker finds a perfect narrative foil to Auden amid the incestuous ranks of the British upper-middle class. Michael Spender was a schoolmate of W. H. Auden and the brother of a different poet, Stephen Spender. An Oxford graduate to John Auden’s Cambridge, a geographer to his geologist, Michael Spender trained in mapmaking and aerial photography in the Alps and went on to land the post that Auden craved, when, in 1935, he was chosen as the chief surveyor for an expedition to reconnoiter Everest.

Auden and Spender weren’t simply among the last Englishmen to be employed by the colonial state. They were among the last propelled into adulthood on a tail wind of imperial self-confidence. They came of age after World War I, when the British Empire was larger than ever on paper, with a clutch of former Ottoman and German colonies transferred into British hands as League of Nations mandates. The British Empire was being managed more liberally, too, with self-government (or “home rule”) having been extended to the so-called white colonies of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and Ireland. Few Britons at the end of the war supported independence for tropical colonies. If anything, they may have expected that a new era of enlightened administration was just getting under way.

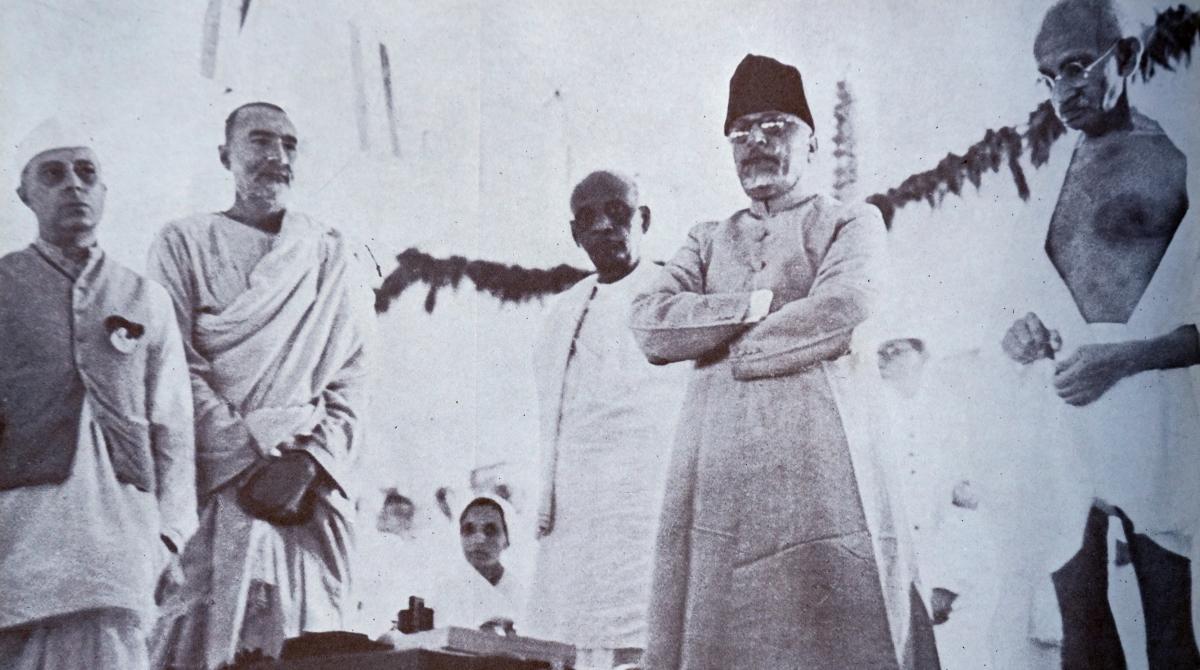

In practice, however, the imperial edifice was cracking under pressure from nationalists—and nowhere more consequentially than in India, the biggest, most valuable colony of all. India had contributed massively to the war effort, and in exchange, Indian political leaders hoped for substantive steps toward home rule. Instead, British administrators granted only moderate reforms, which were offset by enhanced policing of dissent. In 1919, British troops opened fire on a peaceful nationalist gathering in the city of Amritsar and killed nearly 400 unarmed protesters. The massacre galvanized the first India-wide protest led by Mahatma Gandhi, who applied his philosophy of nonviolence to the nationalist cause.

The 1920s and 1930s would be marked by a cat-and-mouse game of protests, crackdowns, and compromises. British authorities jailed independence leaders, then freed them under duress. Gandhi orchestrated ever-larger civil disobedience campaigns and won further legislative reforms. But these still fell short of home rule, and when British authorities unilaterally brought India into World War II, without promising independence in return, the thread of nationalist patience snapped. In 1942, Gandhi called for the British to “quit India” and deliver immediate home rule. By then, the Bengali militant Subhas Chandra Bose was gathering an army, with Japanese support, to drive out the British by force.

A CRISIS OF CONFIDENCE

In any history of British India, these events appear as milestones on the road to independence. In The Last Englishmen, they’re pebbles in the streams of the protagonists’ lives. “If the nineteenth century had been all about piling up one scarcely credible heroic exploit after another,” Baker writes, “the twentieth century . . . seemed to be all about sitting down and taking apart one’s motives.” Auden started psychoanalysis during a furlough in Paris and used his journal writing as a kind of therapy. Spender met the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung on a ship from India and began a course of Jungian analysis.

Auden’s and Spender’s self-examinations reflected a more general crisis of confidence in the imperial system. Another member of the Auden-Spender social circle, Michael Carritt, became a minor district officer in Bengal, where (like George Orwell in Burma) he grew disgusted with the performance of white supremacy. Carritt became an informant for the Communist Party of India and funneled notes to the radical League Against Imperialism in London. His specific trajectory from imperial servant to anti-imperial activist aligns with a broader turn in British opinion. As Gandhi was launching the Quit India movement, the Labour Party passed the Charter of Freedom for Colonial Peoples at its 1942 conference, calling for social equality and democratic government across the empire.

It wasn’t only the British who underwent transformations during these fraught years. Baker also introduces readers to Sudhindranath Datta, a member of Calcutta’s English-educated Indian elite, whose family fortunes had grown in step with British imperialism in Bengal. In 1929, Datta toured the United States with the Nobel Prize–winning poet Rabindranath Tagore, but he returned disgusted both by Western Orientalism and by what he saw as Calcutta’s decay. He started a literary magazine and an adda (salon) in his family mansion in North Calcutta. On Friday nights, between bookshelves with serried volumes of Sir Walter Scott and Alfred Lord Tennyson, the Bengali intelligentsia (and a suspected English police informant) gathered to debate Indian politics and world affairs. The adda acted as a barometer of Indian anticolonialism, where Gandhi’s gradualist vision for independence competed with the ideas of militant rivals, including the Communists and Bose.

Although Auden and Spender are nominally the book’s centerpieces, perhaps the most compelling figure to animate The Last Englishmen is an Englishwoman who connected with them both. Nancy Coldstream, née Sharp, daughter of a Cornish country doctor, moved to London in 1928 to enroll as a student in the Slade School of Fine Art. Canny about the reality that a woman’s path to fortune depended on attaching herself to the right man, she swiftly married the most promising artist in the class, Bill Coldstream. Almost equally promptly, the couple ran out of money and into marital difficulties. Nancy’s time for art making got consumed by caring for an infant daughter. Bill’s creativity sputtered, although he persisted doggedly enough that when he couldn’t find a blank canvas, he took one of Nancy’s best portraits and painted over it “without a second thought.”

Things started looking up for the Coldstreams in 1935, when Bill took a job editing films for the British postal system’s documentary unit and brought a new colleague home to lodge with them: W. H. Auden. Auden and Nancy became fast friends, and through him, Nancy met a series of men who would change the course of her life. First came Auden’s friend Louis MacNeice, a young Irish poet, who fell madly in love with her and began an affair, declaring that “until he’d met Nancy, he’d been color blind.” Then came Auden’s brother John, who was promptly “bewitched” by Nancy. She started an affair with him, too, and promised him her ongoing affections “as long as it doesn’t hurt Louis or interfere with Bill.” It was an impossible calculus, and when John returned to India, his place was taken by another man to whom he himself had introduced Nancy. That, inevitably, was Michael Spender.

Was Nancy Coldstream also a “last”? For all the women’s liberation of the interwar years—including the right to vote and a relaxing of divorce laws in women’s favor—hers was a classic case of a career irretrievably curtailed by marriage and childbearing. And although Baker notes in a postscript that Nancy was “memorialized as one of the most underrated painters of her generation,” the story of her life, at least as described in these pages, is the story of the men she loved. Given how many of the constraints she faced still ring true today, it’s no coincidence that women’s history is more often told in “firsts” than “lasts.”

LOOSE ENDS

Baker has a gift for scene writing and designs the book accordingly, breaking each chapter into segments headed by an address and a date, as if in a play. She conjures up “rippling curtains of rain” draping over the countryside and the “silken currents of the Brahmaputra” running “through loosening skeins toward the Bay of Bengal,” as well as the crush of urban India, where “every veranda held a crowd, every window a curious face” and “grocers slept among vegetables in elevated bamboo huts along crowded roadways.” A trove of wonderfully candid diaries and letters lets Baker get deep inside the characters’ heads and hearts. Reading The Last Englishmen, one can almost screen the television adaptation in one’s head.

But a powerful drama needs its scenes to build into acts, and it’s often hard to know where The Last Englishmen is going—both figuratively and literally. A given chapter might start in a London neighborhood, leap to a Himalayan pass, stop by a Calcutta office, and end up in a Darjeeling boarding house (Chapter 10), or it might open in a Cornish home before staying in a New York hotel, visiting the viceroy’s palace in New Delhi, and attending Datta’s adda (Chapter 14). Baker’s taste for one-line paragraphs enhances the staccato feel. It’s a rhetorical technique that can be very effective in ramping up anticipation or nailing down a point, but here it reads too often as an interruption or an irrelevance.

This is a particular liability when it comes to extracting what, if anything, Baker wants to conclude about the nature of Indian independence. One promise of this book lies in its potential to explore how people make sense of their roles in a system that is failing. Yet for all the vividness of their professional and romantic travails (or perhaps because of it), it is rather difficult to glean how self-conscious Auden and Spender really were about their positions as agents of British power in a period of escalating opposition. Maybe the lesson is a timeless one, that history happens to people far more than people happen to make history. Or maybe it’s that political scruples alone seldom stall the complex engine of life, greased by love, ambition, curiosity, desire, loyalty, anxiety, and hope.

With the onset of World War II, the engine whirred fast and furiously. Nancy Coldstream becomes an ambulance driver. Spender reads aerial photographs for the Royal Air Force. Auden, despite being an amateur flyer, fails the RAF’s pilot test. Meanwhile, in India, violence reaches a new pitch. Japanese bombers strafe Calcutta. Famine devastates Bengal, killing more than three million people; Datta will see the starving straggle into the stairwells of his apartment building to avoid being scooped up by vans sent to drive them out to the countryside to die. When the war ends, the violence does not: in the Great Calcutta Killings of 1946, up to 15,000 people, mostly Muslims, are slaughtered in communal riots.

To give away specific characters’ endings would spoil the plot, but it won’t surprise anyone that the book wraps up with independence in 1947 (at which time, incidentally, Mount Everest had still not been summited, despite the imperial competition of the prewar years). For all that Gandhi had charted a course to freedom on the principle of nonviolence, the independence of India and Pakistan—and the drawing of borders between them—was accompanied by mass migration and horrific violence. This was “liberty and death,” as the cover of Time indelibly put it.

It was neither an Auden nor a Spender who saw the transfer of power up closest; it was their acquaintance MacNeice. Sent by the BBC to report on the transition, he watched celebratory fireworks in New Delhi and interviewed Jawaharlal Nehru, independent India’s first prime minister, before heading to Pakistan. In a refugee camp near the new border, MacNeice encountered the horrifying obverse of freedom: hundreds of men, women, and children “shot, stabbed, speared, clubbed, or set on fire” on their way to India, crammed into a tiny field hospital with just one doctor to attend them. “Night falls on Kipling’s Grand Trunk Road and all the deserted cantonments,” MacNeice wrote in a verse in his diary. “On jute mill and ashram, on cross and lingam . . . / On the man who has never left the forest / On the last Englishman to leave.”

But they didn’t all leave just yet. Early in 1939, Datta had introduced Auden to the woman who finally became his wife. She was a vivacious Bengali painter named Sheila Bonnerjee, and she had recently returned from studying in London. Auden himself was surprised when his mother accepted the news of his marriage to an Indian without batting an eye, “telling him that people treated the subject rather differently nowadays.” The couple’s daughter Anita was born in 1941; a second daughter, Rita, in 1942. I wonder if they would have looked back at a photo of their schooldays and seen it as I did, as empire’s shadow in a postcolonial dawn.

MAYA JASANOFF is Coolidge Professor of History at Harvard University and the author of The Dawn Watch: Joseph Conrad in a Global World.

This article was originally published in the January/February 2019 issue of Foreign Affairs Magazine and on ForeignAffairs.com.