In 1936, Francis Bacon offered some of his works to the International Surrealist Exhibition, but they were rejected as ‘not sufficiently surreal.’ One suspects Bacon would have taken the rebuff in his stride – he always claimed that his pictures were depictions of reality, not sur-reality. The same cannot be said of Salvador Dalí. With his mad moustache modelled on Velázquez’s, his ridiculous antics and his conspicuous consumption, Dalí became synonymous with Surrealism.

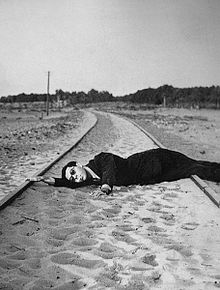

‘Avida Dollars’ (as André Breton liked to call him) had started out broke. When, in 1929, he made a film called Un chien andalou (An Andalusian Dog) with Luis Buñuel, they had to get funding from Buñuel’s mum. What resulted must have severely tested his mum’s maternal loyalties. In the very first moments, she would have watched her burly son sharpening a cutthroat razor before slitting open a woman’s eye. (The eye actually belonged to a dead calf).

Later, a man is seen fondling a young woman’s breasts under her clothing. As if this wasn’t bad enough, the clothing suddenly disappears to show his hands on her bare breasts. Mrs Buñuel must have been in a state of shock by now, but even as she was thinking things couldn’t possibly get worse, the bare breasts turned into naked buttocks. Then the blouse reappeared and the young woman repelled the man’s advances. It would have come as small comfort to learn that her son had not provided the hands in that scene.

In this short film, the two Spanish artists managed to bottle the essence of Surrealism at its most polymorphous perverse. Buñuel’s description of the working relationship between himself and Dalí closely resembles the way Breton describes working with Philippe Soupault. The two Spaniards adhered to a rule: “Do not dwell on what required purely rational, psychological or cultural explanations. Open the way to the irrational. It was accepted only that which struck us, regardless of the meaning ... We did not have a single argument. A week of impeccable understanding. One, say, said: “A man drags a double bass.” “No,” the other objected. And the objection was immediately accepted as completely justified. But when the proposal of one was liked by the other, it seemed to us magnificent, indisputable and was immediately introduced into the script.”

The double bass might have become the violin we see a man kicking along the street before smashing it underfoot, though this violin appears in their second film, L’Age d’Or. It’s hard to know for sure, Buñuel did not have the most reliable memory, as he acknowledged in his autobiography (remind me to read it again someday soon) called My Last Breath, in which he confessed that he could no longer be sure if he had slept with… a certain unattainable Hollywood starlet, I forget who, or if he’d merely fantasised about doing so. Similarly, I recalled vividly that the man who is arrested and frog-marched through the landscape by two well-dressed policemen in that film, manages to break free on spotting a priest and then runs across the road expressly to kick the man of the cloth. In fact, I now discover he doesn’t do anything of the kind. It’s actually a blind man he assaults, and the irascible hero does this in order to board the blind man’s taxi. However, other things I accurately recalled, like the scorpions fighting at the start of the film, or the skeletons of the clergy on the cliffs. In later life, Dalí would blame Buñuel for them.

And who could forget the moment when the heroine gets so randy, she starts sucking the toe of a classical statue?

Back when I watched those films for the first time, it all seemed so exciting. The basic ingredients of the surreal were condensed into a few hours. They were charged with erotic and spooky humour, and far from being wearily familiar, seemed to capture Surrealism at the moment of its inception, gloriously strange, fresh and inventive. At the same time, Dalí and Buñuel had been very conscious of adhering to the tenets of Surrealist theory as outlined by André Breton. In his manifesto, published as recently as 1924, Breton had famously defined Surrealism as:

‘Psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express—verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner—the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern.’

Well, there was no trace of moral concern round here. Apropos his earliest film, which was more effective than a thousand manifestoes, Buñuel recalled how “the aesthetics of Surrealism were combined with some of Freud’s discoveries. The film was totally in keeping with the basic principles of the school, which defined Surrealism as 'Psychic Automatism', unconscious, capable of returning to the mind its true functions, beyond any form of control by reason, morality or aesthetics.”

Given the bomb he was hurling into the midst of bourgeois society, Buñuel was disappointed that the premiere of Un chien andalou did not cause a bigger stir. In fact, the film was a huge success amongst the French bourgeoisie, leading him to exclaim “What can I do about the people who adore all that is new, even when it goes against their deepest convictions, or about the insincere, corrupt press, and the inane herd that saw beauty or poetry in something which was basically no more than a desperate impassioned call for murder?”

L’Age d’Or was a longer work. Charged with the same eroticism, it also had a spooky humour sucked directly from the teat of Dada. There was some semblance of a plot, and the use of classical music lent the whole story a ridiculously portentous air. In the opening scene, for example, the scorpions fight each other to the accompaniment of Mendelssohn’s Fingal’s Cave. No explicit connection exists between this passage of natural history and the ensuing events, but later the trivial disputes at a society gathering are accompanied by the melodramatic chords of Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony. Disconnected from the plot, the final scene shows us de Sade’s depraved characters as they exit the scene of their debaucheries, one of them clearly resembling Jesus. Over the depressing scene pounds a mind-scrambling drum beat that Buñuel remembered from childhood, a beat that would begin on Good Friday and pound day and night in his village, till Christ was risen.

Apart from those drums, it is hard to identify which parts of the film belong to Buñuel and which to Dalí. If Breton’s manifesto compared Surrealism to hashish, this was definitely a shared trip.

The stink of artifice?

René Magritte described the moment when he first saw Giorgio de Chirico’s Song of Love as one of the most moving of his life: “…my eyes saw thought for the first time,” he said. For me, I don’t think there was any precise moment of epiphany such as Magritte described. As I was such a latecomer to the surrealist party, I had already absorbed the surreal by a kind of osmosis from the surroundings, and Magritte himself was one of the people responsible for that process. But the strange picture he had beheld with such a wild surmise in his moment of epiphany actually predated the Surrealist movement. It was painted in 1910 by Giorgio de Chirico, who actually saw himself as a metaphysician, though he would later be embraced by André Breton’s boys as one of their own.

Even without Magritte’s moment of revelation, I seized on Surrealism as an opportunity to think, rather than dream. I was a teenager with hang-ups and tormented by the big questions. The ‘human condition’ had yet to ossify into a cliché, and its paradoxes dogged my every waking thought. Why am I me? Why here? Why now? It was the last tumultuous shout of the inner child’s incessant “Why?” And surrealism, or metaphysics – it hardly mattered what you called it – served the purpose of demanding “Why?” with more pathos than ever before. It showcased the ongoing melodrama of total self-absorption. This same self-absorption afflicted a few of the surrealists too, notably their supreme showman, Salvador Dalí, whose work attracted me more than the others. I even read his self-congratulatory biography, though to be fair to my former self, I found it laughable even then. I just couldn’t resist his soft watches limply draped over branches, his crutch holding up the grotesquely extended hind parts of William Tell, the giraffes on fire for no particular reason.

Disillusion, as in so many things, followed closely on the heels of my idolatry. One week, a young assistant art teacher turned up. He praised my artistic efforts and we got along. One warm spring day, as we strolled around the school grounds together, he gently suggested I extend my range a little. Had I considered abstraction? I said no, I preferred surrealism, really. That was blindingly obvious, he said. “But the surrealists are so hackneyed, their art is incredibly old hat, don’t you think?” Not in the least, I protested, they’ve been an inspiration. “Who do you prefer then? Ernst?” No, I said, I had to say I preferred Salvador Dalí. At this point, the assistant art teacher rounded on me. “Don’t believe the hype!” he said. “That Spanish ‘genius’ is a self-promoting rogue. He’s a complete charlatan. He’s a strutting poseur with a dodgy political agenda. He's quite simply the worst example of commercialised aesthetic prostitution since the sentimentalists of the Victorian era. Dalí,” he concluded, with a conviction I’d never imagined possible, “is a prick!”

This was by no means an unusual or original view; it just wasn’t a view I’d ever heard anyone express before. The rest of the afternoon I could barely concentrate on lessons. In fact, I brooded over what he’d said for days to come. It was just my luck, really, that I’d arrived at the end of the surrealist adventure. My disdain for abstract art may well date from that moment of outraged idolatry. It threw me into a tailspin of artistic self-doubt. I had to review my entire raison d’être. Clearly, the assistant art teacher had no taste. Who was he to sit in judgement? I had a vast range of rhetorical weaponry at my disposal, but the damage was done – the serpent had entered my surreal paradise.

How had the bad odour around Dalí escaped me for so long? The surrealists themselves had seen his flaws, way back before the Second World War, and Pablo Picasso, a fellow Spaniard, wouldn’t even mention his name after Dalí made his peace with Franco – the same Franco whose fascist insurrection had led to the death of the artist’s good friend, the poet Federico Garcia Lorca.

Dali had even renounced Surrealism in the end, so bitter were his relations with the main members of the movement. And among his many critics was, of all people, George Orwell, who certainly knew about a bad odour when he sniffed it. Orwell called him ‘a good draughtsman and a disgusting human being.’ As early as 1944, he wrote of Dalí’s autobiography:

‘It is a book that stinks. If it were possible for a book to give a physical stink off its pages, this one would — a thought that might please Dalí, who before wooing his future wife for the first time rubbed himself all over with an ointment made of goat's dung boiled up in fish glue.’

As so often is the case with Dalí’s confessions, the reader suffers from too much information. Orwell charges the artist with all manner of disgusting proclivities, among them necrophilia, coprophilia, and certain other ‘perversions’ that were more widely frowned upon back in the Forties than they are today. Nevertheless, he acknowledges that he can paint:

‘The two qualities that Dalí unquestionably possesses are a gift for drawing and an atrocious egoism. “At seven,” he says in the first paragraph of his book, “I wanted to be Napoleon. And my ambition has been growing steadily ever since.”

If this was Dalí’s little joke, Orwell is in no mood to find it funny:

‘And suppose that you have nothing in you except your egoism and a dexterity that goes no higher than the elbow; suppose that your real gift is for a detailed, academic, representational style of drawing, your real métier to be an illustrator of scientific textbooks. How then do you become Napoleon?’

He could, Orwell implies, so easily have been trapped by his workmanlike mediocrity. But,

‘There is always one escape: into wickedness. Always do the thing that will shock and wound people… You could even top it all up with religious conversion, moving at one hop and without a shadow of repentance from the fashionable salons of Paris to Abraham's bosom.’

This kind of vitriol is rarely encountered in Orwell’s essays. He tends to be more understated. But of course, beneath the tirade lies a factor in Orwell’s opinion of Dalí that he doesn’t even have to mention – the Spanish civil war. The Englishman’s participation in that conflict had made him hypersensitive to political betrayal. Like Picasso, Orwell could not forgive Dalí for betraying the Republican cause. Consequently, he also can’t forgive him for being ‘as antisocial as a flea’, for pedalling the bogus excuse of his ‘Arab lineage’ for his sybaritic tastes, for hobnobbing with rich people and avoiding the war at the first sign of danger. But most of all, for being on the wrong side when it came to the destiny of his native land. In short, he stinks, which is about as pungent a verdict as that of the assistant art teacher.

Back in his youth, Dalí had been as left-wing as the next surrealist, but when the Thirties arrived, at the beginning of what the poet WH Auden called ‘a low dishonest decade’, he was already suspected of ‘Hitlerian’ sympathies. As early as 1934, Dalí had been subjected to a “trial” by his fellow surrealists and only narrowly avoided being expelled from the group. To this, an unrepentant Dalí retorted “The difference between the Surrealists and me is that I am a Surrealist.” Things got no better as the low dishonest decade wore on. After the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, Dalí avoided taking a public stand for or against the Republic. However, immediately after Franco's victory in 1939, Dalí praised Catholicism and the Falange and was expelled from the Surrealist group. In the May issue of the Surrealist magazine Minotaure, André Breton announced Dalí's expulsion, claiming that he had espoused race war, and that the over-refinement of his ‘paranoiac critical method’ was a repudiation of Surrealist automatism. Around the same time, Dalí painted a picture entitled The Enigma of Hitler, an acknowledgement of the many times the Führer had appeared in his dreams.

Quite possibly some of those dreams, as Breton had suspected, were waking, sexual ones – he had written to André Parinaud confessing homoerotic fantasies:

‘I often dreamed of Hitler as a woman. His flesh, which I had imagined whiter than white, ravished me… There was no reason for me to stop telling one and all that to me Hitler embodied the perfect image of the great masochist who would unleash a world war solely for the pleasure of losing and burying himself beneath the rubble of an empire; the gratuitous action par excellence that should indeed have warranted the admiration of the Surrealists.’

By the time I came across Dalí, this seemed like ancient history. Even the assistant art teacher’s hostility was chiefly focused on his extravagance. Surrealism, in its turn, had become a victim of its own success and was celebrated primarily as having allowed the Unconscious into fine art, its political disputes long forgotten. Freud himself had sat for Dalí in 1936, whispering “That boy looks like a fanatic.” Dalí was delighted upon hearing later about this comment from his hero. The following day, Freud wrote “until now I have been inclined to regard the Surrealists, who have apparently adopted me as their patron saint, as complete fools... That young Spaniard, with his candid fanatical eyes and his undeniable technical mastery, has changed my estimate.” Like Orwell, the grand old psychoanalyst was bewitched by the younger man’s skills as a painter; he was rather less troubled by his dubious politics, if indeed he was aware of them at all.

If Surrealism had once attracted Magritte as a vehicle for thought, it had long since surrendered to its other main preoccupation, with dreams, and it was an association which stuck. Hard to say whether the smelliest of the Surrealists (although money doesn’t smell, as the saying goes) was primarily responsible for this divorce of Surrealism from thinking. His theory of the ‘paranoiac critical method’ had actually come pretty close to the theories in André Breton’s manifesto. Regardless of who was to blame, the style that replaced the movement had lost the political edge it possessed back in the Thirties. We only have to consider the following document from before the Second World War, written by Georges Henein.

The Egyptian Surrealists opposed British colonial rule. They also championed equality of the sexes, unlike their notoriously misogynistic colleagues in Paris. Their manifesto was published under the splendid title Long Live Degenerate Art in defiance of Nazi philistinism. It is worth quoting in full, not least because it is so little known outside Egypt:

‘We know with what hostility current society looks upon any new literary or artistic creation that directly or indirectly threatens the intellectual disciplines and moral values of behaviour on which it depends for a large part of its own life – its survival.

This hostility is appearing today in totalitarian countries, especially in Hitler’s Germany, through the most despicable attacks against an art that these tasselled brutes, promoted to the rank of omniscient judges, qualify as degenerate.

All the achievements of contemporary artistic genius from Cézanne to Picasso – the product of the ultimate in freedom, strength and human feeling – have been received with insults and repression. We believe that it is mere idiocy and folly to reduce modern art, as some desire, to a fanaticism for any particular religion, race or nation.

Along these lines we see only the imprisonment of thought, whereas art is known to be an exchange of thought and emotions shared by all humanity, one that knows not these artificial boundaries.

Vienna has been left to a rabble that has torn Renoir’s paintings and burned the writings of Freud in public places. The best works by great German painters such as Max Ernst, Paul Klee, Karl Hoffer, Kokoschka, George Grosz and Kandinsky have been confiscated and replaced by Nazi art of no value. The same recently took place in Rome where a committee was formed to purge literature, and, performing its duties, decided to eliminate works that went against nationalism and race, as well as any work raising pessimism.

O men of art, men of letters! Let us take up the challenge together! We stand absolutely as one with this degenerate art. In it resides all the hopes of the future. Let us work for its victory over the new Middle Ages that are rising in the heart of Europe’ (Cairo, 22 December 1938).

Notable by his absence from Henein’s list: the one and only Avida Dollars. There would have been no such righteous indignation from one of Europe’s most prominent surrealists. Indeed, his lurch towards the far right gives us some reason to wonder if Dalí could still be considered a Surrealist at all. Certainly, he himself was no longer so sure. He began to see himself as a ‘classicist’ instead.

Matters came to a head in the spring of 1941, when he exhibited at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York. Declaring himself no longer a Surrealist, for good measure he announced the death of the Surrealist movement and the return of Classicism. The exhibition included nineteen paintings, among them Slave Market with the Disappearing Bust of Voltaire:

...and The Face of War.

In his catalogue essay for the New York exhibition, Dalí proclaimed a return to form, control and structure. Sales, however, were disappointing and the majority of critics did not believe there had been a major change in Dalí's work.

But the paintings were clearly intended to proclaim his continued relevance; there is even a hint at a social conscience in the depiction of war, and the evanescent Voltaire, champion of Liberty, makes perfect sense in the context of a slave market.

However, appearances (as anyone familiar with Dalí will know) can be deceptive. He was a kind of Morrissey of the art world, spouting and pontificating at the slightest provocation. After returning to his native Catalonia in 1948, he publicly supported Franco's regime and announced his embrace of the Catholic faith. He had official meetings with General Franco in June 1956, October 1968, and May 1974. In 1968, Dalí stated that on Franco's death there should be no return to democracy and Spain should become an absolute monarchy, and by the following year he was boasting: “Personally, I'm against freedom; I'm for the Holy Inquisition.”

* ‘Surrealism Beyond Borders’ is at Tate Modern till 29th August 2022.